Executive Summary:

This research paper examines the reality of the Syrian family during the post-conflict transitional phase. It presents a comprehensive vision for formulating a just and sustainable social policy focused on rebuilding the family as a central unit in restoring the national fabric, achieving social justice, and promoting citizenship.

The paper adopts an analytical and descriptive methodology, based on a review of academic literature, United Nations reports, and studies published by Syrian and international research centers. It is divided into six main chapters:

- Chapter One frames the theoretical concepts related to the family, analyzes its functions and transformations during the conflict, and highlights its role in transitional justice.

- Chapter Two describes the current reality of the Syrian family, from its fragmented structure and shifting roles to the weak legal and social protection, especially in conflict zones and the diaspora.

- Chapter Three reviews the challenges facing decision-makers, such as the absence of a national database, legal divisions, weak institutions, and the politicization of social policies.

- Chapter Four proposes a transitional social policy based on the principles of justice and equality, including reform of the personal status law, support for affected families, and the integration of the family into transitional justice programs.

- Chapter Five links national family policies to the United Nations system, through alignment with international agreements and sustainable development goals, and activating cooperation with UN agencies.

- Chapter Six presents executive recommendations on behalf of the Syrian Future Movement, including legal reforms, the establishment of an independent national body, the launch of support programs, the activation of community participation, and adherence to international standards.

The paper argues that rebuilding the Syrian family is not merely a social issue, but rather a national and humanitarian mission that requires political will, community cooperation, and international partnership to establish a new social contract that guarantees dignity and justice for every individual in Syria.

Introduction:

The family is the fundamental pillar in building societies and the primary source of socialization, instilling values, and shaping national identity.

In the Syrian context, which has witnessed a bloody conflict and widespread institutional collapse over the past decade, the family has emerged as one of the social structures most vulnerable to disintegration and pressure, as a result of displacement, detention, killing, poverty, and political and regional divisions.

As Syria enters a transitional phase after decades of tyranny, there is an urgent need to reconsider social policies related to the family, as a cornerstone in rebuilding the national fabric, restoring identity, and achieving social justice.

International studies have shown that armed conflicts lead to profound transformations in the structure and functions of the family. The proportion of female-headed households is increasing, early marriage and domestic violence are widespread, education declines, and intergenerational bonds are weakened.

In the Syrian case, these challenges are compounded by the absence of effective social policies, the overlap of legal references between civil and religious, and the ongoing political division that hinders the unification of legislation and institutions.

This paper aims to provide Syrian decision-makers with a comprehensive research framework on ways to rebuild the family during the transitional phase. This framework is based on analyzing the current reality, reviewing the challenges, and proposing just and sustainable social policies based on international human rights standards and consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the President of the Transitional Phase, President Ahmad al-Sharaa, particularly Goal 5 on gender equality and Goal 16 on peace, justice, and strong institutions.

The paper adopts an analytical and descriptive methodology, based on a review of relevant academic literature, United Nations reports, and studies published by Syrian and international research centers. It also analyzes existing policies and compares them with transitional experiences in other countries.

The paper also seeks to link the legal, social, and political dimensions of the family and provide applicable implementation recommendations within the Syrian context.

The paper is divided into six main chapters, beginning with a framework for theoretical concepts, then moving on to a description of the current reality and identifying challenges. It then presents a vision for the required policies, linking them to the United Nations system, and concludes with a conclusion and practical recommendations.

Rebuilding the Syrian family is not just a social issue. It is a national, political, and humanitarian matter that requires genuine will and cooperation between state institutions, civil society, and international partners to establish a new social contract that guarantees dignity, justice, and citizenship for every individual in Syria.

Chapter One: Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

The Syrian Family in the Transitional Context: Concepts, Functions, and Transformations:

The family is a central social unit in the formation of societies. It is the primary incubator of values, identity, upbringing, and social control.

In the Syrian context, the family gains double importance due to its historical role in maintaining societal cohesion in the absence of effective state institutions, especially during the years of conflict since 2011.

As Syria enters a transitional phase, the need arises to frame the concepts associated with the family, define its functions, and analyze the transformations it has undergone. This will enable decision-makers to formulate social policies that respond to reality and establish a sustainable future.

First, the definition of the family in the Syrian context:

Syrian law defines the family as “the legitimate bond that arises from marriage and includes the spouses and their children,” according to the Personal Status Law of 1953 and its amendments.

However, this legal definition does not reflect the actual diversity of the Syrian family structure, especially in light of displacement, migration, and the multiplicity of legal authorities across areas under different authorities.

There are extended families, single-parent families, undocumented families, and families living in the diaspora, all of which constitute a social reality that must be taken into account in transitional policies.

Second, the functions of the family in Syrian society:

The family in Syria performs multiple functions, including:

- Socialization: instilling religious and national values and shaping cultural identity.

- Economic support: sharing resources and providing protection from poverty, especially in the absence of formal safety nets.

- Social control: monitoring behavior and resolving conflicts within the local community.

- Psychological and moral care: providing support in cases of loss, trauma, and displacement.

Successive crises have demonstrated that the Syrian family, despite its fragility, has been able to partially perform these functions, making it a key player in the recovery and reconstruction phase.

Third, the transformations that have occurred in the Syrian family:

The Syrian family has witnessed profound transformations during the years of conflict, most notably:

- The disintegration of the family structure: due to killing, detention, and displacement, leading to an increase in the percentage of families headed by women or children.

- The change in traditional roles: Women have been forced to assume the roles of breadwinner, community leadership, and education, in the absence of men.

- The decline in educational functions: due to the dropout from education, psychological breakdown, and the spread of violence.

- The weakening of intergenerational ties: due to diaspora, political division, and the difference in cultural norms between the country and abroad.

These transformations require decision-makers to reconsider family policies, going beyond traditional legal definitions and taking into account the complex and changing reality.

Fourth, the family as an actor in transitional justice:

Transitional justice cannot be discussed without involving the family, as it is the primary victim of violations and the primary incubator of victims.

Families who have lost children or suffered violations need recognition, compensation, and participation in policy formulation to ensure the non-recurrence of violations and establish true societal reconciliation.

Families can also be a tool for reconciliation by transmitting values and educating generations on tolerance, justice, and citizenship. This requires support through comprehensive educational and social policies.

Chapter Two: The Current Reality of the Syrian Family

The Disintegration of Structure, Changing Roles, and Protection Challenges in Light of Conflict and Transition:

During the years of conflict since 2011, the Syrian family has witnessed profound transformations that have not been limited to its formal structure, but have also affected its functions, the roles of its members, its internal relationships, and its position within the legal and social system.

As the country enters a transitional phase, the need for a precise understanding of the current reality of the family emerges. This will enable decision-makers to formulate social policies that respond to the challenges and establish a sustainable recovery phase.

First, the Disintegration of the Family Structure:

The conflict has led to the widespread disintegration of the Syrian family structure, as a result of killing, detention, displacement, and asylum. This has led to the emergence of new types of families, most notably:

- Single-parent families: where women or children assume the responsibility of providing for the family after the loss of a father or husband.

- Forced Extended Families: As a result of displacement, several families have been forced to live in one home, creating social and psychological pressure.

- Undocumented families: Due to the absence or inaccessibility of civil records, especially in conflict zones or diaspora areas.

This structural disintegration has led to a decline in the family’s ability to perform its traditional functions and created new challenges in the areas of education, protection, healthcare, and upbringing.

Second, the changing roles within the family:

The conflict has resulted in a radical shift in roles within the Syrian family, most notably:

- The rising role of women: Women have been forced to assume the roles of breadwinners, educators, negotiators, and community activists in the absence of men.

- Children’s early responsibilities: Due to poverty or the loss of a breadwinner, children have been forced to work, care for their siblings, or engage in unsafe activities.

- The decline of traditional paternal authority: Due to diaspora or political division, this has led to a weakening of internal control within the family.

These transformations, although they have demonstrated social resilience, have also revealed the fragility of the family structure and the lack of institutional support to ensure its stability.

Third, Legal and Social Protection Challenges:

Syrian families face significant protection challenges, most notably:

- Lack of unified legislation: Personal status laws vary across regions and are subject to varying religious and political influences.

- Weak social protection networks: There are no effective national programs to support affected families, female heads of households, or unaccompanied children.

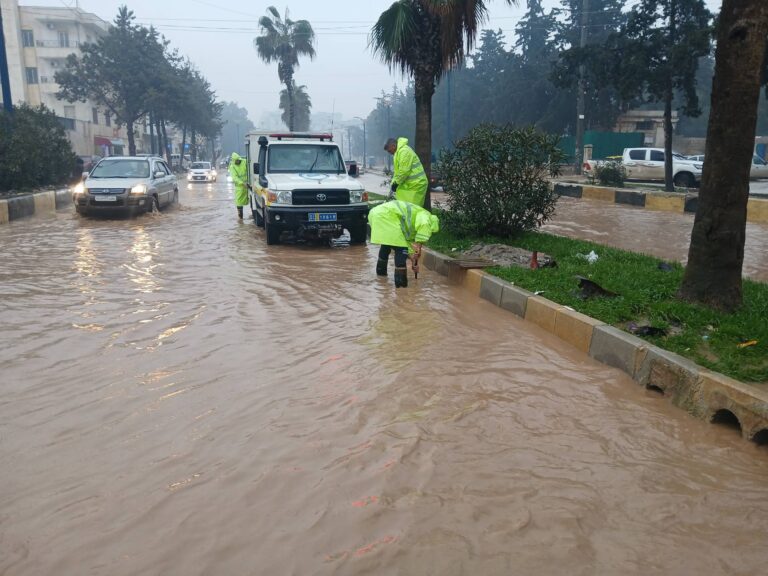

- Lack of access to basic services: In conflict zones that continue after Assad, or in camps, families suffer from a lack of education, healthcare, and psychological support.

- Legal discrimination against women and children: Some laws still perpetuate discrimination in custody, inheritance, and guardianship, weakening family protection.

These challenges require comprehensive reform of social policies, legislation, and institutional structures to ensure family protection as a fundamental component of societal reconstruction.

Fourth, the family in diaspora and asylum:

In countries of asylum, Syrian families face additional challenges, including:

- Cultural integration: The difficulty of reconciling Syrian values with local laws.

2- Legal threats: such as loss of custody or deportation due to non-compliance with the law.

3- Family division: as a result of individual migration or refusal to reunite, leading to the disintegration of family ties.

These challenges impact national identity and weaken ties between the home and abroad, requiring policies that connect the diaspora to the homeland and ensure family protection in all its locations.

Chapter Three: Challenges Facing Decision-Makers

Institutional Void, Legal Division, and Weak Social Protection in Managing the Syrian Family Issue:

In the context of the transitional phase that Syria is undergoing after decades of tyranny and bloody conflict, decision-makers face complex challenges in dealing with the family issue, which is one of the most sensitive and complex issues.

Rebuilding the Syrian family requires not only legal or institutional reform, but also a comprehensive vision that addresses the effects of conflict, political division, institutional vacuum, and the deterioration of the social structure.

This chapter highlights the most prominent challenges hindering the formulation of a fair and sustainable family policy in the new Syria.

First, the absence of an accurate national database:

One of the most prominent challenges facing decision-makers is the absence of a unified and comprehensive database on Syrian families, especially those affected by the conflict. There are millions of internally displaced families, others in the diaspora, and families who have lost their breadwinner or a family member, without a central registry documenting their conditions, needs, or legal status. This absence hinders planning and renders social policies haphazard or ineffective.

The political division between different areas of control has also led to multiple and conflicting databases and a lack of coordination between official and unofficial bodies, weakening the ability to respond to families’ actual needs.

Second, the legal and legislative divide:

The Syrian family today is subject to multiple legal authorities, which differ between areas controlled by the central government and those administered by local authorities or political factions, such as Sweida and Jazira. In some areas, the amended Syrian Personal Status Law applies, while other areas rely on laws derived from Sharia law, local custom, or even laws imported from the experiences of countries of asylum.

This legal division leads to:

- Disparities in the rights of women and children from one region to another.

- Difficulty in unifying procedures for marriage, divorce, custody, and inheritance.

- Lack of legal guarantees to protect families from violations or discrimination.

This challenge is one of the most serious obstacles to developing a national family policy and requires a comprehensive legal dialogue to unify these authorities and ensure their compatibility with international human rights standards.

Third, weak social and institutional protection:

Syrian families suffer from a near-total absence of social safety nets, whether in the areas of financial support, healthcare, education, or psychological support. Relief programs, despite their importance, remain temporary and limited and do not constitute a substitute for a comprehensive national policy.

Institutions concerned with family affairs, such as the Ministry of Social Affairs and local councils, also suffer from a lack of resources, coordination, and qualified personnel, rendering their interventions unsystematic or unsustainable.

In this context, the absence of specific programs to support:

- Female-headed households.

- Children without legal or social support.

- Families who have lost a family member due to conflict or detention.

- Families in conflict zones or camps.

Fourth, the impact of political division on policy unity:

The family issue cannot be separated from the broader political context, as the division between political forces has led to the politicization of social policies and their use as a tool of influence or control. Some parties impose family laws or programs that serve their ideological or sectarian interests, threatening societal unity and undermining trust in institutions.

The lack of national consensus on transitional priorities also makes it difficult to include the family issue on the reform agenda, allocate the necessary resources, or involve civil society in policy formulation.

Fifth, weak community participation in policy formulation:

Although the family is a fundamental societal unit, policies related to it are often formulated without the active participation of citizens, civil society organizations, unions, or human rights organizations. This exclusion leads to unrealistic, unworkable, or unpopular policies. The next parliament may be a starting point for this.

Therefore, involving local actors, especially women, in formulating family policies is a prerequisite for the success of any social reform during the transitional period.

Chapter Four: Towards a Just Transitional Social Policy

A Rights-Based and Developmental Approach to Rebuilding the Syrian Family in the Post-Conflict Phase:

There is a clear need today to formulate a new social policy that addresses the family as a fundamental unit in rebuilding society, restoring the national fabric, and achieving social justice.

This policy must be transitional in nature, meaning it must respond to the post-conflict reality, take into account the effects of war, and establish a lasting phase of stability and dignity.

First, the founding principles of the transitional social policy:

For family policy to be effective and just, it must be based on a set of principles, most notably:

- Justice and equality: guaranteeing the rights of all family members, regardless of gender, religion, or social background.

- Recognizing harm: formally acknowledging the violations families have suffered and including this in reparation policies.

- Responding to changing realities: taking into account the shifts in family structure, roles, and needs, and not relying solely on traditional models.

- Linking law and social policy: Unifying legal references and updating legislation in line with international standards.

Second, reforming the Personal Status Law:

The Personal Status Law is one of the laws most impactful on the family and requires a comprehensive review that includes:

- Eliminating discrimination against women in custody, guardianship, inheritance, and marriage.

- Unifying legal references across different regions and adopting a comprehensive national civil formula.

- Including protection of children from early marriage, domestic violence, and economic exploitation.

- Facilitating civil documentation procedures for unregistered families, especially in conflict zones and diaspora areas.

Third, supporting families affected by conflict:

Families that have lost a family member, have been displaced, or are headed by women or children require special support programs, including:

- Direct financial assistance for families with breadwinners.

- Psychological and social care services for victims and survivors.

- Compensatory education programs for children who have dropped out of school.

- Comprehensive health insurance for families in affected areas.

These programs must be managed by independent national institutions, in cooperation with civil society organizations and international bodies.

Fourth, Integrating the Family into Transitional Justice Programs:

The family issue cannot be separated from the transitional justice process. It is essential to:

- Involve families in documentation and recognition processes of violations.

- Customer-led collective and individual reparations processes for affected families.

- Include families as direct beneficiaries of community reconciliation programs.

- Include families’ stories in the new national narrative, enhancing cohesion and mutual recognition.

Fifth, Strengthening the Role of the Family in Building Citizenship:

For the family to be an effective player in building the new Syria, it must be empowered educationally and culturally through:

- Integrating civic education into educational curricula and linking it to the role of the family.

- Organizing community awareness campaigns on family rights, equality, and justice.

- Supporting local initiatives that promote dialogue within families and rebuild trust among community members.

Chapter Five: Linking with the United Nations System

Integrating National Family Policies with International Standards and Sustainable Development Goals:

In the context of building a new Syria, social policies cannot be separated from the international system, which has established clear standards for protecting the family, promoting social justice, and achieving sustainable development.

The United Nations system, including its specialized agencies, is a key reference for formulating a transitional family policy that guarantees rights, takes into account the local context, and draws on comparative experiences in post-conflict countries.

First, International References Related to the Family:

The United Nations provides a set of agreements and recommendations that constitute a legal and ethical framework for protecting the family, most notably:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948): It stipulates the right of everyone to form a family and to live in a safe and dignified environment.

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989): It obliges states to protect children within the family and to guarantee their right to education, care, and not to be separated from their parents except when necessary.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW): Emphasizes equality within the family and women’s right to make family decisions without discrimination, despite reservations by Islamic countries.

- The UNESCO Recommendation on Education for Global Citizenship (2015): Links the role of the family to fostering values of peace, justice, and pluralism.

These references form the basis for formulating a Syrian family policy that aligns with international obligations and strengthens Syria’s position within the global human rights system.

Second, Related Sustainable Development Goals:

The family is a key axis in achieving several of the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations for 2030, most notably:

- Goal 1: Eradicating poverty – by supporting vulnerable families and providing social safety nets.

- Goal 3: Good health and well-being – by ensuring maternal and child health care.

- Goal 4: Quality education – by empowering families to support children’s education.

- Goal 5: Gender equality – by reforming family legislation and empowering women within the family.

- Goal 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions – by integrating the family into the transitional justice and reconciliation process.

Aligning Syrian family policies with these goals is a strategic step toward building a just and stable society and enhances opportunities for international cooperation and technical and financial support.

Third, opportunities for cooperation with UN agencies:

The transitional phase in Syria provides an opportunity to activate partnerships with UN agencies, particularly:

- UNICEF: to support child protection within the family, and provide education and psychosocial care.

- UNFPA: to promote reproductive health, support women heads of households, and combat domestic violence.

- UNDP: to develop social policies and build institutional capacity.

- UNHCR: to protect families in the diaspora and ensure their legal and social rights.

These agencies have extensive experience working with post-conflict communities and can be key partners in developing a comprehensive Syrian family policy.

Fourth, Challenges in Policy Alignment:

Despite the importance of linking with the United Nations system, there are challenges that must be addressed, most notably:

- Internal political divisions that hinder the unification of legal references.

- Weak institutional structures that prevent the effective implementation of international programs.

- Cultural and religious sensitivity toward some international concepts, such as gender equality or protection from domestic violence.

- The lack of a unified political will to adopt radical reforms in the family file.

These challenges require a comprehensive national dialogue and careful coordination between government agencies, civil society, and international partners.

Chapter Six: Conclusion and Recommendations

The Syrian Future Movement’s Vision for Rebuilding the Family in the New Syria:

After reviewing the theoretical framework, analyzing the current reality, identifying challenges, proposing policies, and linking them to the international community, it becomes clear that the Syrian family issue is one of the most sensitive and important issues in the transitional phase.

The family is not only a social unit; it is the primary incubator of identity, justice, and citizenship. It is the party most affected by the conflict and the most important actor in reconstruction.

The Syrian Future Movement, as a national movement that believes in a civil Syria based on justice and equality, believes that rebuilding the family must be a priority in transitional policies. As we presented our vision in previous theses published on our official website, particularly the study entitled “The Syrian Family After Liberation: Towards Building a New Society Based on Freedom and Equality,” published in Mansoura on March 10, 2025, we, in the Family Affairs Office of the Syrian Future Movement, offer the following recommendations to Syrian decision-makers and relevant national and international bodies:

First, reform the Personal Status Law:

- Drafting a unified civil personal status law that guarantees gender equality, protects children’s rights, and takes into account cultural and religious diversity without discrimination.

- Repealing articles that perpetuate discrimination or weaken family protection, particularly with regard to custody, guardianship, inheritance, and early marriage, in a manner that does not conflict with Syrian and religious culture. This is the task of the next parliament.

Second, establish an independent national body for family affairs:

- Establish an independent body tasked with monitoring the conditions of affected families, providing legal and social support, and coordinating policies between government agencies and civil society.

- Ensure the body’s independence from political or security influence, and link it to a transitional or interim legislative council.

Third, launch a national program to support affected families:

- Allocate financial resources to support single families, families who have lost a family member, and families in conflict zones or diaspora.

- Provide psychological care services, compensatory education, and health insurance, in cooperation with international organizations.

Fourth, integrate families into the transitional justice process:

- Officially recognize the violations families have suffered and document them in transitional justice files.

- Allocate collective and individual compensation processes, including financial support, rehabilitation, and participation in policy formulation.

Fifth, engage civil society in family policy formulation:

- Open the door for civil society organizations, unions, and human rights organizations to participate in policy formulation and monitor its implementation.

- Support local initiatives that promote dialogue within families and rebuild trust among community members.

Sixth, align national policies with international standards:

- Commit to relevant United Nations conventions, especially the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

- Link family policies to the Sustainable Development Goals and activate partnerships with relevant United Nations agencies.

Finally, building a new Syria cannot be achieved without rebuilding the family, as the primary incubator of justice, citizenship, and coexistence.

The Syrian Future Movement believes that this task is not merely technical or legal, but rather a national and moral one, requiring political will, community cooperation, and international partnership to establish a new social contract that guarantees dignity for every individual and restores Syrians’ confidence in themselves and their country.

References:

- Al-Khatib, Nader. (2022). The Syrian Family in Times of War: A Social Field Study. Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies.

- Center for Legal and Social Studies – Paris. (2020). Redefining the Family in the Contexts of Conflict and Political Transition. Center Publications.

- Center for Citizenship and Social Studies – Gaziantep. (2023). Rebuilding the Syrian Family: A Legal and Development Approach. An Analytical Study.

- Syrian Women’s Network. (2022). Reforming Personal Status Law in Syria: Towards Gender Justice. Network Publications.

- Syrian Center for Policy Research (SCPR). (2022). Fragmentation and resilience in Syria: Social trends and policy gaps. Retrieved from https://www.scpr-syria.org/

- Syrian Center for Policy Research (SCPR). (2023). Socioeconomic impact of the Syrian conflict on families. Retrieved from https://www.scpr-syria.org/

- UNDP. (2023). Social protection in fragile states: Comparative insights from Syria. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/

- UNFPA. (2023). Families in crisis: The impact of conflict on household structures in Syria. Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/

- UNICEF Syria. (2023). Family and child protection in post-conflict Syria. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/syria/

- UNHCR & UNICEF. (2022). Protection needs of Syrian families in displacement and return. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/

- International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). (2021). Families and reparations: Integrating social policy in transitional justice. Retrieved from https://www.ictj.org/

- Buecher, B., & Aniyamuzaala, J. (2016). Women, war and the family: Gendered impacts of conflict. International Review of the Red Cross, 98(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383117000423

- Save the Children. (2021). Child labor and family breakdown in conflict zones: The Syrian case. Retrieved from https://www.savethechildren.org/

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from https://sdgs.un.org/

- World Bank. (2021). Data gaps and policy challenges in post-conflict societies. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/