Introduction:

Syria in 2025 is witnessing the repercussions of a decade and a half of armed conflict and mass destruction, making reconstruction a complex task that goes beyond restoring infrastructure to rebuilding social security and national identity.

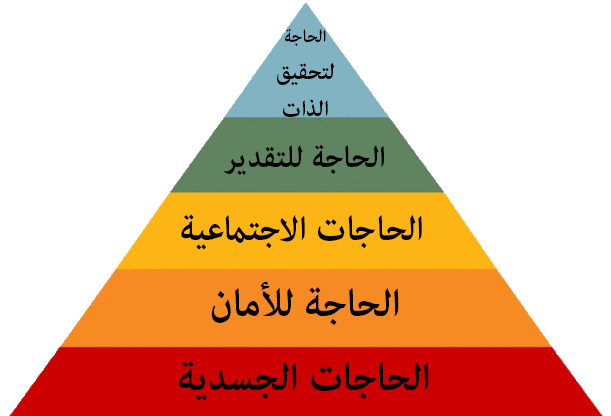

In this context, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a powerful analytical framework for understanding post-conflict development priorities. It is based on the fundamental principle that levels of belonging, esteem, and self-fulfillment cannot be achieved without first securing physiological and security needs.

This paper aims to explore the role of Syrian foreign policy in securing the base of Maslow’s hierarchy, enabling the country to attract international funding to rebuild basic infrastructure (food, water, housing, safety) and subsequently move to higher levels of social stability and political participation.

Theoretical Framework: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in the Context of Reconstruction.1

Abraham Maslow devised the Hierarchy of Human Needs in 1943 as a matrix that analyzes human motivations, starting with basic physiological needs, moving on to physical and psychological security, social status and esteem, and finally self-actualization.

Although Maslow’s model was originally designed to analyze individual motivations, international development researchers have adopted it to explain the priorities of post-conflict countries, as good governance and political participation cannot be achieved without ensuring basic needs for citizens.

The theoretical framework’s standing in post-conflict literature has been strengthened by studies that have observed that societies that neglect the first levels of the hierarchy (such as food, shelter, and safety) have failed to build resilient social and political institutions.

In Syria, where years of war have destroyed the basic services network and reshaped the sectarian and geographic sphere of influence, the model becomes a tool for mapping priorities:

First, securing the physiological needs of food and water security, then building local security forces capable of enforcing the rule of law, before embarking on transitional justice programs and engaging the community in decision-making.

Basic Needs Assessment: The Humanitarian Situation in Syria 2025.2

2.1 Physiological and Nutritional Needs:

According to a report by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 16.5 million Syrians need urgent humanitarian assistance, including 6.8 million internally displaced persons.

Data indicates that nearly half of the country’s population suffers from varying degrees of food insecurity, while the international response covers only 15.9% of funded needs for 2025.

Norwegian Relief reports that power outages and a shortage of water pumps have made sanitation vulnerable to the spread of epidemics, exacerbating the suffering of displaced people in camps and destroyed homes. This gap in the fulfillment of physiological needs prevents them from moving to higher levels of the pyramid, such as a sense of belonging or social integration.

2.2 Safety and Stability Needs:

Internal security is a fundamental pillar of Maslow’s hierarchy and determines a citizen’s ability to feel personal safety and secure their livelihood.

The Spokesperson for the Secretary-General at the Security Council documented that 670,000 people were displaced during the first half of 2025 due to renewed violence in areas such as rural Damascus and Sweida, and that dozens of small cities are subjected to intermittent shelling despite official truces.

The International Monetary Fund also confirms that the collapse of the economic system and the lack of cash liquidity leave citizens vulnerable to the black market and organized crime, necessitating the restructuring of the security, gendarmerie, and police services to ensure state authority throughout Syria and reduce violations against civilians.

Foreign Policy and Securing International Funding for Reconstruction.3

3.1 Relations with the United States and the Role of Sanctions

Despite the US administration’s reservations about engaging with Damascus, early 2025 saw discussions in Congress about partially lifting the economic sanctions imposed to allow the entry of humanitarian supplies and the rehabilitation of infrastructure.

This shift is seen as a test case for restoring diplomatic confidence, as lifting sanctions requires the Syrian government to commit to a fair distribution of aid and not exploit it for political or sectarian purposes.

3.2 Debt Settlement and Relations with Saudi Arabia:

Riyadh played a pivotal role in alleviating Syria’s debt burden with the World Bank through an initiative it sponsored in Riyadh in mid-2025, which opened the door to credit facilities for Syrian companies to rehabilitate hospitals and schools in liberated areas.

This was accompanied by monthly financial support for the public sector and direct grants to civil servants in the amount of $30 per month, which somewhat mitigated the inflationary unemployment rate and gave initial indications of Saudi Arabia’s desire to regain its regional position as a relief and investment actor.

3.3 The Turkish Role and Reconstruction in the Northern Regions:

Ankara contributed to launching joint projects with Damascus to rehabilitate hundreds of kilometers of rural roads in the provinces of Aleppo, Hasakah, and Raqqa, in partnership with Saudi and European investors.

Experts provided preliminary estimates that these projects could reduce internal transportation costs by up to 30%, restoring the luster of agricultural activity and light industries in northern Syria.

3.4 Talks with Israel and their Impact on Southern Stability:

In the south, sponsored by Washington and blessed by Tel Aviv, indirect talks led to the establishment of a truce agreement in the Golan Heights, with international monitors present to ensure both sides’ adherence to the ceasefire. This truce, despite its violation by Israel through its incursion into Quneitra, has allowed for the opening of limited humanitarian crossings and the entry of construction materials to repair several border schools and hospitals. The Syrian government has used this as a first step to build bridges of trust with the international community.

Security Challenges and Security Sector Reform.4

4.1 Force Training and Equipment Modernization:

Sources highlight that more than 1,800 Syrian security personnel underwent intensive training in Qatar and Saudi Arabia, as part of a 45-day program for each category, which included security skills,Crisis management and dealing with civil society groups.

This movement came within a regional context seeking to replace security systems based on party loyalty with professional entities operating under civilian supervision.

4.2 Accountability and Trust Building:

Carnegie Endowment studies indicate that training personnel alone is not sufficient. Rather, judicial and civil mechanisms must be established to hold security violations accountable and provide citizens with effective channels for grievance redress.

The absence of accountability perpetuates the cycle of violence and reduces the chances of society moving to higher levels of Maslow’s hierarchy, such as self-esteem and achievement.

From the Base of the Pyramid to Rebuilding National Identity.5

5.1 Social Belonging and National Cohesion:

Once security is restored and basic needs are met, the next challenge is to build a new social fabric that transcends sectarian and ethnic divisions.

Local reconciliation committees and village councils are participatory tools that have contributed to resolving architectural and tribal disputes in rural Homs and Deir ez-Zor, supported by microfinance programs launched by UN agencies and civil society organizations.

5.2 Valuing and Self-Realization: Transitional Justice and Political Reform

When the state moves to implement transitional justice programs, citizens are able to restore their dignity and realize their rights to reparations and political participation.

An initiative overseen by the Justice Transition Commission has documented thousands of cases of enforced disappearances and launched independent investigative committees. This initiative has laid the foundations for expressing community anger through legal means, enhancing a sense of justice and belonging.

Policy Recommendations.6

In light of the above, we in the Political Bureau of the Syrian Future Movement recommend the following:

Strengthen international coordination by forming a multilateral working group comprising UN, regional, and Western.7 organizations to coordinate reconstruction efforts and ensure that Syrian parties commit to directing resources to basic needs first.

Reform the security sector by integrating regional training programs with organizational and structural mechanisms to hold.8 violations accountable and provide ongoing human rights training.

Launching micro-development programs that engage local communities in setting their priorities and managing projects,.9 enhancing community ownership of initiatives and improving levels of belonging and appreciation.

Linking transitional justice with humanitarian relief by creating mixed units comprising legal and psychological experts to10 document violations and provide psychological and social support to victims as they access reconstruction services.

11.Following up on financial reforms by granting Damascus gradual economic incentives in exchange for meeting specific standards of transparency and anti-corruption, with the goal of gaining donor confidence and achieving sustainable economic growth.

Conclusion:

The Syrian experience in 2025 demonstrates how applying Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can provide a roadmap for the most pressing reconstruction priorities, starting with meeting physiological and security needs, moving on to building a strong social fabric and implementing transitional justice.

In this context, foreign policy becomes the primary mechanism for attracting international funding and ensuring coordination of regional and international efforts. By addressing basic needs first, Syria can open the door to higher levels of sustainable development, leading to a stable and prosperous society built on solid humanitarian foundations.

References:

- Arab Democratic Center. (2023). The Problem of State-Building After the Revolutions: The Syrian Case as a Model. Berlin: Arab Democratic Center for Publishing and Studies.

- Roya for Thought and Studies. (2024). Political, Economic, and Humanitarian Challenges in Post-Revolution Syria. Amman: Roya Foundation for Thought.

- Al Jazeera Center for Studies. (2025). Political Transition in Syria: Between Reality and Ambition. Doha: Al Jazeera Center for Studies.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- Brunckmann, J., & Kizilhan, J. I. (2017). Psychological needs and integration of Syrian refugees in Germany. Journal of Refugee Studies, 30(3), 456–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fex027

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2025). Syria humanitarian needs overview. https://www.unocha.org/syria

- Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). (2025). Rebuilding Syria: challenges and priorities. https://www.nrc.no/reports/rebuilding-syria-2025

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025). Syria: Economic outlook and reconstruction needs. https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/SYR

- Carnegie Middle East Center. (2024). Syria’s foreign policy and reconstruction: Between isolation and engagement. https://carnegie-mec.org/2024/03/15/syria-foreign-policy

- Atlantic Council. (2025). A roadmap for Syria’s stabilization: International task force proposal. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/report/syria-stabilization-roadmap

- Human Rights Watch. (2025). Reforming Syria’s security sector: Accountability and professionalization. https://www.hrw.org/report/2025/04/10/syria-security-reform