Syria at a crossroads:

Before the revolution, Syria faced both economic and institutional challenges. It suffered from a weak and fragmented institutional structure, widespread corruption and favoritism, a high poverty rate, and rising unemployment.[i] For example, according to the Doing Business Indicators[ii] in 2009, Syria ranked 136th out of 181 countries globally, while Turkey ranked 78th, Jordan 106th, and Egypt 109th.

After 14 years of war and destruction that have turned Syria into a failed state, with the economy in decline and infrastructure collapsing by more than 60%, the country stands on the brink of collapse. The transitional government, in a desperate attempt to revive the economy, is rapidly adopting policies based on opening up strategic sectors such as electricity, oil, and gas to private investment and privatizing what remains of the public sector.

Although the transitional government has not officially announced its economic direction and plan, nor has it clarified how ownership will be distributed between the public and private sectors; Nor has it officially published details of the contracts that have been signed or are being negotiated. Therefore, the announced measures demonstrate a clear bias toward an extreme neoliberal model. This article claims that applying this prescription in the current Syrian circumstances is not only a mistake, but a dangerous slope that will lead to the squandering of the country’s wealth and guarantee the state’s future failure.

Neoliberal Economics: The False Promise

Economic neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that favors free-market capitalism with minimal government intervention. It emphasizes privatization, deregulation, free trade, and reduced public spending to promote economic growth. It also emphasizes economic globalization, which entails the free movement of capital across international borders.

Here, it must be distinguished from traditional liberal capitalism, which is based on the protection of private property, a free market governed by supply and demand without significant government intervention, and a reliance on profit as the driver of production and investment, thus driving competition and thus improving the product and lowering prices. The state has a relatively limited role to play. In other words, the fundamental difference between the two is the extent of the state’s role in intervening in formulating the country’s general strategic policies and enacting laws and regulations. In traditional capitalism, the state retained powers that enabled it to ensure the functioning of infrastructure, social security for the people, and even control monopolies. While in neoliberalism, the role of the state has declined in favor of large corporations, and large corporations have broader powers in shaping even international policies. For example, during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, Western governments provided generous financial support to rescue the large corporations that caused the crisis, while reducing their support for the common people who were victims of the crisis.

A simple illustration of the difference between the two systems:

“If traditional capitalism is like an old-fashioned restaurant where the owner sells whatever he wants, and the customer buys or doesn’t buy, while the state is merely a policeman at the door,

neoliberalism is like a global restaurant chain buying up small restaurants, imposing its rules on everyone, and telling you, ‘If you don’t like it, don’t buy it; you’ll only find what you want here.’ Here, the state is merely a receptionist who opens the door.”

Neoliberalism’s intellectual origins go back to economists like Milton Friedman, who saw free markets as the only guarantee of political freedom and economic efficiency. The first entrenchment of this system, with government support, occurred during the Reagan era in America and the Thatcher era in Britain. Neoliberalism quickly spread to Western Europe beginning in the 1990s and accelerated further at the beginning of the third millennium.

However, the implementation of these policies on the ground, especially in fragile economies, revealed their ugly face. Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize laureate in economics, summarizes the failure of economic neoliberalism in his book Globalization and Its Discontents: “The IMF’s neoliberal policies, such as rapid privatization and fiscal austerity, were a recipe for social and economic disaster in many developing countries, exacerbating poverty rather than solving it.”

Neoliberal Economics: Between Success and Failure:

“Success” itself is a term that can be measured in various ways: aggregate economic growth versus social justice, rising GDP versus the well-being of the average citizen. In short, the results have been mixed to mostly negative for the developing world. While some countries have achieved growth, this growth has come at a high social and economic cost.

First: Arguments for “Success” (The Limited Model)

Neoliberalists defend its success in some countries on the basis that it played a significant role in:

- Combating hyperinflation: Austerity policies and the removal of subsidies imposed by the International Monetary Fund helped curb hyperinflation in countries like Argentina and Brazil in the 1990s.

- Attracting foreign investment: Liberalizing markets and privatizing certain sectors attracted foreign direct investment to countries like Mexico after NAFTA and Chile under Pinochet, considered the first neoliberal experiment.

- Economic Growth in Asia: Some analyses suggest that economies like China and Vietnam (despite their political socialism) have embraced neoliberal elements such as openness to global markets and special economic zones, leading to massive economic booms.

However, these successes are superficial and controversial. For example:

- Chile’s economic success came at the price of bloody repression and massive social inequality.

- Growth in China and Vietnam was under the control and direction of a strong state, not the full liberalization of the market advocated by extreme neoliberalism.

Second: Failures and Criticisms (Conventional Opinion)

Here we come to the crux of the matter. The vast majority of analyses, especially from development experts, view the application of the neoliberal prescription to the developing world as disastrous for several reasons:

- The IMF and World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), the primary mechanism for disseminating neoliberalism[i], imposed harsh conditions:

- Privatization of public utilities: The sale of energy, water, telecommunications, transportation, and other sectors to foreign or domestic investors, resulting in higher prices for the poor and lower quality of service. This is what David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession.” [ii] Accumulation by Dispossession”

- Cutting social spending: Imposing cuts in spending on health, education, and social services to achieve “budget balance.” This destroyed social safety nets and increased poverty rates. Joseph Stiglitz strongly criticizes this in “Globalization and Its Dissenters,”[iii] arguing that these policies completely ignored social needs.

- Sudden trade liberalization: Opening markets to subsidized foreign imports (such as European or American agricultural products) destroyed nascent local industries and traditional agriculture in Africa and Latin America. Local farmers could not compete.

- Inequality worsened: The growth achieved was not inclusive. Wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few. Thomas Piketty, in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, explains how capital liberalization policies increased the concentration of wealth.

- Dependence and fragility: Developing economies became more dependent on global fluctuations and mobile capital, making them more vulnerable to crises, as in the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

- Disappointment in Latin America: The experiences of Argentina and Brazil in the 1990s led to debt crises and economic collapses (Argentina’s 2001 crisis). This failure paved the way for the rise of the leftist wave (“left turn”) in that continent in the first decade of the 21st century, as a reaction to neoliberalism.

Ultimately, the alleged success is a dubious success, based on formal dazzle, but often leading to disastrous results, especially in developing countries. Neoliberalism did not achieve a comprehensive development “miracle” in the developing world. Instead, it:

At best, it achieved quantitative growth, but at the expense of social stability and equity.

It increased the fragility and dependency of economies.

It deepened class disparities and impoverished the middle and lower classes.

The prevailing academic view, as embodied by the writings of Ha-Joon Chang[iv], is that countries that truly developed (such as former South Korea and current China) did not follow the neoliberal prescription to the letter, but rather employed a strong developmental state that intervened to support emerging industries and direct investment. Their neoliberalism was “directed,” not “savage.”

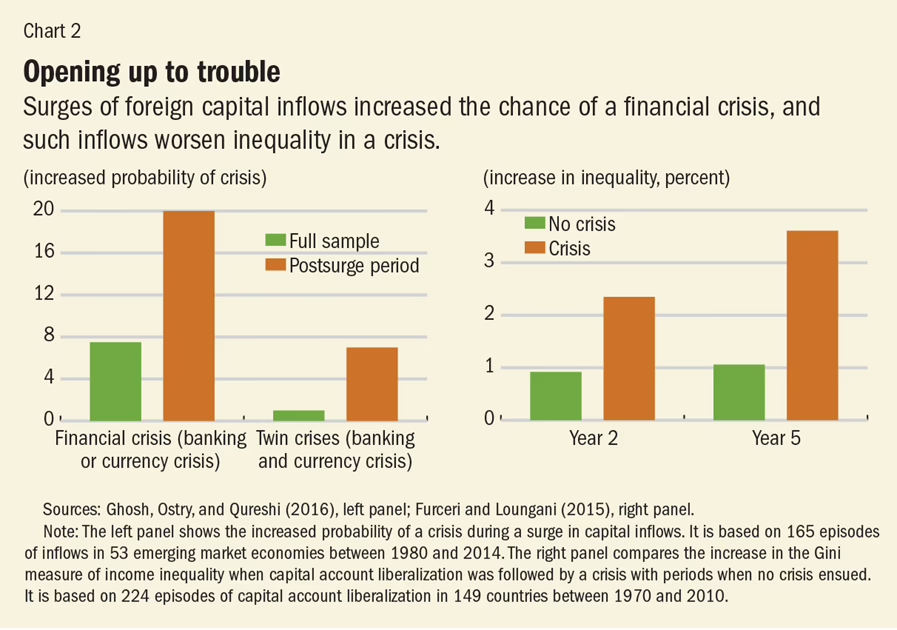

Figure 1: The risk of economic crises compared to countries that experienced economic growth based on foreign investment flows. The left-hand figure shows the increased likelihood of a financial crisis. The two left-hand columns show that the probability of a banking or monetary crisis is two and a half times greater than the entire sample studied; the two right-hand columns show that the probability of a combined (banking and monetary) crisis is seven times greater. Meanwhile, the right-hand figure shows that the Gini index, which measures inequality, is higher in emerging economies and increases significantly after five years (Reference 3).

Figure 1 is one of the results of numerous economic studies around the world, which warn that pursuing a neoliberal approach (rapid privatization, uncontrolled capital liberalization) is a proven recipe for failure. This figure is one of the results of a study presented by experts at the International Monetary Fund itself.

The Costly Lesson of Europe: When Neoliberalism Reshapes the Continent

Neoliberalism’s failure was not limited to the developing world. At the heart of Europe itself, austerity policies and the privatization of services led to devastating consequences, particularly for critical sectors of economic and social infrastructure.

The French Experience: Privatization Ended with a Return to the State

In France, governments since Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency have begun selling shares in Électricité de France (EDF) to the private sector. The goal was to reduce the burden on public finances and promote competition. But over time, a fundamental problem emerged: private investment focused on quick profits, while neglecting costly, long-term investments in nuclear infrastructure. When the European energy crisis erupted following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Paris had no choice but to renationalize the company entirely, in a practical admission that the market alone could not protect national energy security.[1]

Russian Gas: Market Before Security

At the European level, the contradiction became even more apparent. Before 2022, natural gas imported from Russia accounted for approximately 42% of the European Union’s imports, while Germany’s share exceeded 50%. This is despite the fact that energy security guidelines recommend that reliance on any one supplier should not exceed one-third of total imports.[ii] Of course, the decision to take this risk was made by private energy companies, which preferred to import Russian gas because it was cheaper. In other words, market logic prevailed over strategic security logic. When the war broke out, Europeans faced severe shortages and skyrocketing prices, exposing the fragility of an energy infrastructure based on market reliance without oversight and state protection of the public interest.[iii]

These two experiences demonstrate that neoliberalism may work in some sectors, but it is dangerous in strategic sectors such as energy. The private market is concerned with short-term profit, while energy security requires a long-term vision and investments that may not be immediately profitable. For this reason, France was forced to return to the state, and Europe was forced to search in a frantic race for alternative gas sources and new LNG infrastructure.

The European energy crisis has once again reminded us that the state is not the obstacle, as neoliberalism portrays it, but rather a fundamental guarantor of stability and energy sovereignty. From the privatization of EDF to the Russian gas crisis, the lesson is clear: when you leave strategic infrastructure solely in the hands of the market, you put even the strongest economies at risk.

Lessons from Developing Countries:

- Iraq after 2003, Privatization as a Weapon of Occupation: US “civilian administrator” Paul Bremer imposed radical neoliberal policies, including the wholesale privatization of the public sector and the elimination of subsidies. The result: the Iraqi economy became a failed rentier economy, local industry collapsed, and wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few, fueling sectarian conflict and violence. Joseph Stiglitz summarized this by saying that shock therapy was the most extreme of all, greatly contributing to the increase in sectarian rifts and significantly hindering reconstruction in Iraq.[i]

- Lebanon, the neoliberal bubble that burst: The uncontrolled privatization and financial liberalization system, led by Rafik Hariri, created an economy based on services, banking, and corruption.[ii] This fragile model tragically collapsed in 2019, leading to one of the world’s worst financial crises since the nineteenth century, as citizens were deprived of their deposits and basic services collapsed. Here, it must be noted that Rafik Hariri’s policy, in terms of form, presented impressive projects and achieved a relatively short-term economic boom. This is one of the characteristics of economic neoliberalism when implemented relatively quickly. It initially achieves impressive economic growth, which may be palatable to the public, but in the medium and long term, this policy leads to deep and difficult-to-solve economic problems.

- Turkey, Unsustainable Economic Growth: Despite the apparent rapid growth of the Turkish economy until 2010, this growth did not strengthen the Turkish economy to deal with market and political fluctuations.[iii] Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s calculated neoliberal policies (which strengthened the influence of major contractors and investors close to the government) led to massive inequality, erosion of the industrial sector, and excessive reliance on foreign investment, imports, and foreign debt. The severe economic crisis sweeping Turkey today, with rampant inflation and the collapse of the lira, is the inevitable result of an economy not built on truly productive foundations and a sustainable economic structure that possesses the flexibility and strength to withstand the fluctuations of the global economy and the tensions of geopolitical relations.[iv]

In all of these examples, neoliberalism has produced fragile wealth for a few, and destabilizing poverty and instability for the majority. These are evidence of the failure of neoliberal economic policies in the developing world. Many other countries, such as Brazil and Argentina, have followed this policy, often as a result of pressure from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The Negative Consequences of Economic Neoliberalism in Developing Countries:

Why does economic neoliberalism lead to such poor outcomes for the majority of the population, despite the recommendations of major financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund?

The answer to this question can be summarized in several fundamental, indisputable points:

- Most people in developing countries suffer from high poverty rates, institutional weakness, and rampant corruption and favoritism. The relationship between political systems and society is based primarily on political patronage. The quality of the relationship between local social groups and the central government affects the national integration and regional organization of the various regions.

To develop the national economy, the local market must first be able to respond to national production, both in terms of participation in production and consumption. That is, the consumer must be relatively strong. To achieve this improvement in individual consumer power, these countries require state intervention and oversight, ensuring an improvement in citizens’ purchasing power.

However, the private sector is not interested in achieving this improvement in purchasing power within the country itself, because the dominance of globalization may replace private investment with stronger consumer markets.

- Infrastructure projects, such as electrical power systems, including power plants, transmission and distribution networks, transportation networks, roads, railways, and other infrastructure, telecommunications networks, the education sector, and the health sector, typically require significant investments. These projects must also be built according to strategic plans that may prioritize the needs of these facilities over profit.

Effective state involvement in these sectors can prioritize providing services to citizens in a sustainable, efficient, and high-quality manner.

However, private investment prioritizes high and rapid profitability, avoiding costly development and maintenance whenever possible. It also prioritizes investments that are more profitable and secure, which may conflict with the state’s economic strategy.

- The experiences of all developing countries, especially those similar to Syria, confirm that the decline of the state’s regulatory, guaranteeing, and oversight role increases the level of corruption and favoritism.

- As previously mentioned, the national economy’s dependence on foreign investment, even local private investment, makes the country’s economy extremely sensitive and vulnerable to international economic crises. This is what we have observed in the multiplying effects of economic crises on developing countries, including economically emerging countries such as the Gulf states and Turkey, compared to their impact on the rich countries that caused these crises.

Here, it is necessary to clarify, so as not to confuse concepts. Criticism of economic neoliberalism is not a leftist position or orientation, as some might think. It therefore becomes a mere disagreement, or perhaps an understatement, between right and left, or between capitalism and leftism. Criticism of economic neoliberalism has come from the majority of Western academics and economic researchers, from both the left and the right. For example, the proposal here is not against the free market in its classical sense, which emerged in Western Europe after World War II, Japan and South Korea, and even China, two decades ago, began to introduce the principle of the free market.

Syria: Why Privatization Now Is a Fire Sale

With a collapsed state, a collapsing currency, and ineffective institutions, selling off the Syrian public sector is like selling off family assets in a moment of desperation. It would be neither fair nor strategically profitable. Instead, the country’s strategic assets would end up being seized, while it is in a state of extreme weakness and chaos, in what economists call “accumulation by dispossession.” This means that the gains will accumulate in the pockets of:

- Local oligarchy[i]: This will consolidate a corrupt system based on quotas and favoritism, transferring the country’s wealth to a few individuals and groups.

- Foreign investors with political agendas: This will deprive Syria of sovereignty over its resources and make it a hostage to external political and economic powers.

This will lead to a failure in financial stability and ensuring development and economic sustainability, because the proceeds from selling the public sector and strategic assets are temporary and will not address the structural imbalance plaguing the state. Consequently, social services, such as health, education, and housing, will continue to collapse. This explains the term “fire sale,” an economic term that refers to the sale of goods at a low price during times of crisis. The term literally means “fire sale,” referring to the fact that some people are forced to sell their goods at very low prices due to a major fire.

This is not merely a position or a difference in economic vision. Rather, the experiences of many developing countries, and countries that have experienced similar situations to what Syria has experienced in recent history, provide us with horrific evidence and examples of the consequences of this policy.

The Syrian Transitional Government’s Approach:

Mr. Sharaa, the head of the transitional government, has repeatedly stated that he embraces this economic approach. Although his statements are unclear as to whether he is referring to traditional capitalism or economic neoliberalism, he has focused more on his conviction that state support for basic goods and the public sector is a failed policy, based on its failure during the rule of the two former Assads.

Most importantly, the transitional government has practically moved toward neoliberalism by overstepping its authority and beginning to sell off the public sector, including the energy sector, arbitrarily dismissing a large number of public sector employees and the entire army and security forces of the former regime. This has also been accompanied by the announcement of several contracts with foreign entities, including the ports of Latakia and Tartous, among others. This is not to mention the announcement of several dazzling projects, including towers, media cities, and commercial centers, which are not commensurate with the income level of the majority of Syrians.

The transitional government announced a massive contract, initially valued at $7 billion, with foreign private companies to build 5,000 megawatt power plants.[ii] In addition, several meetings between the Syrian transitional government and foreign oil and gas companies have been announced, and reports have emerged of negotiations with Syrian billionaire Ayman Asfari regarding Syria’s natural gas sector.

The transitional government’s apparent move to negotiate with major international companies to invest in the oil and natural gas sector carries a significant risk: these companies will prefer to export to the global market because of its more profitable prices, regardless of the need for Syria to maintain a strategic reserve of oil and natural gas for as long as possible. The size of Syria’s oil and natural gas reserves represents a significant amount for a country with a population of approximately 25 million, allowing it to export a portion of these natural resources. However, over-exporting oil and natural gas will accelerate the depletion of these reserves, thus transforming Syria into an importer rather than an exporter within 10 or 15 years.

The Dominance of Ad hoc Policies and the Lack of Strategic Planning:

Sustainable development depends on the stability, strength, and sustainability of three interconnected and interdependent pillars: political stability, economic sustainability, and human development. Economic sustainability necessarily requires a strong, dynamic, reliable, inclusive, scalable, and expandable economic infrastructure.

Given that economic infrastructure is the most important factor in the performance of any economic system, in terms of efficiency, reliability, and sustainability, and given that more than 60 percent of Syria’s economic infrastructure has been completely or partially destroyed, developing a roadmap based on a reliable and scalable methodology represents the first and most important step in the reconstruction process. Therefore, establishing the basic outlines of a roadmap for rebuilding Syria’s economic infrastructure and defining the objectives, workflow, and tools within an integrated project is an essential and necessary step at this stage in Syria’s history.

However, in the absence of a roadmap for a strategy to rebuild Syria’s infrastructure[i], the policies taking place in Syria, which rely solely on a vision for the coming years, represent an economically ill-calculated adventure, closer to improvised policies by the standards of nation-building after major disasters. Strategic planning (30 to 50 years) is a necessity imposed by the massive destruction of infrastructure.

If we compare the Syrian situation with those in Turkey, Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon, we can assert that this economic policy will lead to a superficial economic boom and a surge in investment figures that will dazzle ordinary citizens. It will also lead to the emergence of dazzling buildings such as towers, hotels, and restaurants that may reach the level of dazzling buildings in Istanbul and New Cairo. However, it will significantly increase the poverty of the Syrian majority. More importantly, it will lead to the emergence of a fragile economy, vulnerable to regional and international political and economic changes, and to the loss of the state’s independence from foreign investment sources.

The Alternative: The Path of the Developmental State:

The cure for Syria’s reconstruction is not more shocks. The alternative is to adopt the “developmental state” model, which successfully rebuilt countries like Germany and Japan after World War II, and in the renaissance of South Korea.

Definition of a developmental state:

A state in which the government assumes a direct leadership role in directing the economy to achieve ambitious and rapid development goals, beyond merely correcting market failures. It is not a socialist state (owning the means of production), but it is also not a purely liberal state that leaves everything to the market.

Main points:

An efficient bureaucracy and elite:

- There is a strong administrative apparatus that is relatively independent from political pressures and private interests.

- Civil servants, especially in powerful economic ministries (such as the Ministry of Industry and Trade), are highly qualified and selected based on merit (often graduates of top universities).

- This “bureaucratic elite” plans and implements the development strategy.

State autonomy:

- The state has the “autonomy” to make difficult, long-term decisions that may conflict with the short-term interests of certain groups (such as large landowners or certain businessmen).

- The state can “impose” its development vision on society.

A clear developmental vision

- The state develops a clear strategic plan for economic transformation, usually focusing on industrialization as the main path to breaking out of underdevelopment and building a strong economy.

- The goal is to catch up with developed countries by adopting “leading industrial” strategies that lead other sectors.

Strategic Alliance with Business

- The relationship here is neither one of complete state control nor one of complete liberalization of the business sector.

- The relationship is a guiding partnership: the state provides protection, support, and credit to selected sectors, and in return imposes strict performance standards (such as increased exports and technology transfer).

- The basic mechanism is “getting the prices wrong” (i) (ii), where the state intervenes to direct capital through easy, smart, institutional, and strategic credit toward specific sectors, rather than letting the market determine “getting the prices right.”

This mechanism may not be foolproof and may even be dangerous, as happened in Egypt with government subsidy policies, and as happened in Syria with the Assad regime’s policy of setting the pound at a value far removed from its true market value.

However, with intelligent, disciplined, and thoughtful government management, it has yielded results that serve the national goal of giving the national economy the required economic boost. This deliberate distortion of prices is often corrected. This is what happened in South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, as attested to by the World Bank in its report “The East Asian Miracle 1993.”

Focus on Export-Orientation

After a period of protecting emerging industries, the state is aggressively pushing these industries into global markets to test their efficiency and ensure their continued development. Export is the primary criterion for a company’s success.

Difficulties of Implementation in the 21st Century:

The success of this model occurred under specific historical and political circumstances (the Cold War, Western support for the fight against communism, and relatively authoritarian regimes that facilitated decision-making). Its implementation in the 21st century has become more complicated due to globalization and World Trade Organization (WTO) rules that limit protectionist and subsidy policies.

A More Flexible Economic Alternative:

The developmental state model can be leveraged and the neoliberal economic model can be avoided. The developmental state is indeed a powerful alternative, but its implementation in the 21st century context, especially in a country emerging from war and destruction like Syria, requires intelligent adaptation that learns from past successes and overcomes present-day challenges.

The main challenges facing the developmental model today are: globalization, WTO rules, the dominance of global value chains, the digital revolution, and environmental challenges. However, these challenges can be transformed into opportunities in the following ways:

From “Traditional Manufacturing” to “Smart and Specialized Manufacturing”

Opportunity: Instead of trying to compete with large countries in cheap mass production, focus on specialized and technologically advanced industries that rely on human capital.

Syrian Application: Syria has a history in medicine, engineering, and computer science. A development strategy can be built around:

- Pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries: Exploiting and building on a previous scientific base.

- Software and information technology: A less expensive investment than heavy industries and relies on human skills.

- Renewable energy: Turning the electricity crisis into an opportunity to build a local solar energy industry.

- 1.2.2 Guiding Partnerships in the Era of Globalization: “Smart Partnerships” Instead of “Closed Protectionism”

Challenge: The World Trade Organization prohibits overt protectionism and direct financial support.

Solution: Use permitted and innovative tools:

Support for research and development (R&D): This is permitted and encouraged globally. Establishing public-private research institutes based on the Taiwanese ITRI model to develop local technologies.

Quality, health, and safety standards: Use them as an indirect tool to protect emerging industries while raising their quality.

Promoting exports through logistics and information services: Providing global market information to emerging exporters instead of direct financial support.

Leveraging global value chains instead of fighting them.

Old strategy: Building a complete local industry from the ground up.

New strategy for Syria: Integrating into a specialized segment of the global value chain. The goal is not to produce a complete car, but rather to become a reliable exporter of high-quality auto parts or specialized electronic components for European, Turkish, or Asian companies. This ensures the entry of hard currency and the transfer of knowledge.

Absolute Priority: Institution Building (Governance First):

This is of utmost importance in the Syrian context. The success of the development model depends on a “competent and honest bureaucracy.” The most dangerous thing is implementing interventionist policies under weak and corrupt institutions, as this will lead to patronage, corruption, and theft of public funds, and will kill any chance of success.

The first step for any transitional government must be reforming the judiciary, enhancing transparency, and combating corruption as an absolute priority before any major economic intervention. Without this foundation, any model—neoliberal or developmental—will fail.

Social Justice as a Foundation for Stability, Not a Luxury:

The classic development model has sometimes sacrificed social justice for rapid growth. This is dangerous in post-conflict Syria; therefore, integrating the social dimension into the reconstruction strategy and launching the economic recovery is an absolute necessity. Social protection programs and investments in health and education must be an essential part of the development strategy, not a complement to it. Rebuilding people is more important than rebuilding stones.

Roadmap for Establishing Economic Policy in Syria

The priority must be rebuilding the state and society, not maximizing profits. Therefore, policy must be directive and intelligently interventionist, not liberalizing, which will be difficult to prevent in the near future.

Policies are formulated according to a well-thought-out, scientific roadmap that combines emergency planning (1 to 3 years), medium-term planning (5 to 10 years), and long-term planning (40 to 60 years). This planning is essential because reconstruction involves building infrastructure with a lifespan of at least 40 years (7).

Stages of Administrative and Economic Recovery:

In the first five years, the problem of assuming that the transitional government will remain in place for five years becomes clear. During this period, work can be roughly divided, rather than sharply, according to the following stages:

Phase One: Emergency and Relief (1-2 years)

- The Central Role of the State: The state must remain the primary distributor of resources through massive relief programs (funding from international organizations and Gulf and European countries with political guarantees).

- Partnership with the Small Local Private Sector: Encourage small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in agriculture, local food production, and handicrafts. Provide small loans at zero interest.

- Reform the Public Sector, Not Sell It: Rehabilitate hospitals and public schools, and pay the salaries of employees (teachers, doctors) to restore a minimum level of services.

Phase Two: Reconstruction and Stabilization (3-5 years)

- Tax System Reform: Establish a fair, progressive tax system (the rich pay more) to finance public services.

- Attracting productive investments: Encouraging investment in manufacturing and agriculture, not just imports and consumption.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): This is the best model for sectors such as electricity and oil.

- Ownership of resources (such as oil and natural gas) remains with the state (owned by the people).

- The state contracts with a private company (local or foreign) with technical expertise for an operation and management contract (O&M) or a build-operate-transfer (BOT) contract for a power plant.

The fundamental difference: The state controls the final price, receives a share of the profits, and maintains sovereignty over the resource.

Stage Three: Growth and Development (after 5 years)

Only here can discussions begin on the privatization of some non-strategic sectors, after building strong regulatory bodies capable of preventing monopolies and protecting consumers, and establishing an open market based on strength rather than necessity.

Conclusion: It is not permissible to gamble with Syria’s future in the face of the difficult reality.

In the Syrian context, where societal divisions remain deep, the privatization of resources may not just be an economic adventure, but a spark for new political and regional divisions. The danger is not only economic, but also social, political, and perhaps even security-related.

Syria is not a bankrupt company that can be dismantled and its parts sold. It is a nation with a legacy and a deserving future. A neoliberal economy based on rapid privatization at this moment of weakness is a gamble with the future of Syria and future generations, with high-risk transactions, as the experiences of other countries around the world have proven.

Success will not come from the prescriptions of a brutal market, but from a political will that places institution-building and social justice in parallel and at the heart of the reconstruction process. The lesson from Europe, Iraq, and Lebanon is clear: the neoliberal path is a dead end. Syria must choose a different path, that of a strong and just state that builds, not sells.

the reviewer:

- سورية حتى العام 2011، ما بين الابن وأبيه، علاء الخطيب، المركز العربي لدراسات سورية المعاصرة، 29 كانون الأول/ديسمبر ,2022 https://www.infosalam.com/syria/syria-studies/syria_to_2011#_edn6

- تقرير “اقتصاد الأزمة السورية” – صندوق النقد الدولي – حزيران 2016

- Neoliberalism: Oversold?، Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri، Finance & Development, June 2016, Vol. 53, No. 2 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm

- Harvey, D. (2004). “The ‘new’ imperialism: accumulation by dispossession”. Socialist Register. 40: 63–87.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2002). Globalization and its discontents. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393051247.

- ها جون تشانغ Ha-Joon Chang عالم اقتصاد بريطاني من كوريا الجنوبية ، متخصص في اقتصاديات التنمية، ويعمل كقارئ في الاقتصاد السياسي للتنمية بجامعة كامبريدج.

- Le Monde, “EDF to be Renationalized Amid Energy Crisis,” July 2022

- International Energy Agency (IEA), Energy Security in Europe, 2022

- Thomas Pellerin-Carlin, The European Energy Crisis: From Market Failure to Public Responsibility, Jacques Delors Institute, 2022.

- Economic Restructuring in Iraq: Intended and Unintended Consequences، Yousif, B. (2007)، Journal of Economic Issues, 41(1), pg.44 http://www.jstor.org/stable/25511155

- . The reconstruction of Lebanon or the racketeering rule، Fabrice Balanche، 25 September 2024|

https://www.fabricebalanche.com/en/lebanon/the-reconstruction-of-lebanon-or-the-racketeering-rule/ - Turkey in the Global Economy: Neoliberalism, Global Shift, and the Making of a Rising Power، Bülent Gökay، McGill-Queen’s University Press، ISBN 9781788210843

- Neoliberal Politics in Turkey، The Oxford Handbook of Turkish Politics، Pages 159–186، Sinan Erensü, Yahya M. Madra، 02 September 2020

- حكم الأقلية أو الأوليغاركية أو الأوليغارشية (بالإنجليزية: Oligarchy) هي شكل من أشكال الحكم بحيث تكون السلطة السياسية محصورة بيد فئة صغيرة من المجتمع تتميز بالمال أو النسب أو السلطة العسكرية.

- أسئلة حول غموض عقد الكهرباء السوري، علاء الخطيب، 14 حزيران\يونيو 2025 https://www.infosalam.com/syria/syria-articles/electricity_contract

- إعادة الإعمار الاستراتيجي في سورية: تحويل التحديات إلى فرص، علاء الخطيب، 12 كانون أول\ديسمبر 2024 https://www.infosalam.com/syria/syria-studies/strategic-reconstruction-syria

- [1] Six Getting Relative Prices “Wrong”: A Summary، South Korea and Late Industrialization Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization، Alice H. Amsden، Pages 139–156https://doi.org/10.1093/0195076036.003.0006

- Getting the Prices Wrong https://doi.org/10.1093/0195076036.003.0006أو تحديد الأسعار بشكل خاطئ يعني تحديد أسعار غير صحيحة للسلع أو الخدمات أو عوامل الإنتاج (مثل العمل، رأس المال، الأرض) — إما عن طريق التدخل الحكومي أو التشوهات السوقية — مما يؤدي إلى تخصيص غير فعال للموارد في الاقتصاد. وضمن هذا السياق تعبر عن تدخل ال