By the Syrian writer: Yassin al-Haj Saleh

In the ashes of silence left by the tyrant’s fall, the revolution did not end; rather, its true nature began to unfold. The Syrian revolution, in its early days, was a cry for dignity emanating from the throats of ordinary people. Then, under the hammer blow of the three monsters, it transformed into an open wound and a bleeding memory. But the wound was merely a seed.

Today, after the throne of tyranny crumbled in December 2024, the question is no longer: How did Assad fall?

The question now is: What do we make of all this bloodshed and the hope that has been lost?

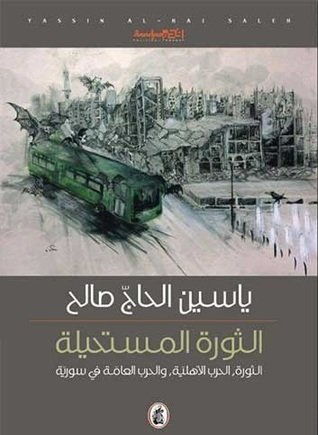

“The Impossible Revolution” by Yassin al-Haj Saleh is a book to be read as an intellectual roadmap for anyone who wants to build a future and not reproduce the past.

In every line, he reminds us that the revolution was forced to wait until the necessary awareness matured, an awareness capable of protecting it from both its enemies and its own children. We read it today to draw inspiration on how to transform wounds into strength, memory into a national project, and pain into a new constitution for a Syria that will not return to tyranny, will not fall into the trap of sectarianism, and will not surrender its fate to any external monster.

Because, ultimately, the revolution is an open question: Do we deserve to be free?

The answer lies in what we will build tomorrow from its spiritual, intellectual, and human legacy. Therefore, we open this book.

Book Information

- Title: The Impossible Revolution: Revolution, Civil War, and General War in Syria

- Author: Yassin al-Haj Saleh, a Syrian leftist thinker and political dissident, spent 16 years in the prisons of the Assad regime (1980–1996). He is considered one of the most prominent critical voices of the Syrian revolution and its transformations.

- Publisher: Arab Institute for Studies and Publishing, Beirut.

- First Publication Date: 2017 (First Edition).

- Number of Pages: Approximately 288–312 pages (depending on the edition).

- Nature: The book is a collection of essays originally written in Arabic between 2011 and 2016, compiled and published as a single volume. An edited English translation, “The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy” (Hurst Publishers, London 2017, translated by Ibtihal Mahmood), is also available.

The book offers a critical chronological analysis tracing the revolution’s trajectory from a peaceful uprising to a multi-dimensional war, focusing on the social, cultural, and political roots of the tragedy.

The book’s narrative and analytical approach:

Hajj Saleh begins with an introduction in which he describes the revolution as having “occurred” despite its seeming impossibility under a regime built on preventing change indefinitely. In the introduction to this edition, he states: “The Assad state was built on the premise that revolution was impossible, change was impossible, and the status quo would prevail forever. Society was riddled with intelligence services and sectarian fears.” This quote encapsulates the core vision: the regime was designed to stifle any radical change, initially rendering the revolution “impossible,” before it transformed into a multifaceted tragedy.

In his early essays (circa 2011–2012), he focuses on the uprising as a “people’s” revolution, a moral and cultural revolution before it was political. He describes how it sprang from the bodies of ordinary young people demanding dignity, far removed from sectarianism or jihadism. He rejects the official narrative that portrayed it as a foreign conspiracy, asserting that the violence originated with the regime, and that the revolution was an expression of a long-suppressed society yearning for its moment of release.

As repression intensified, he shifts to analyzing the mechanisms of state violence. He dedicates essays to “the Shabiha and their state,” explaining that the Shabiha are an organic extension of the state, embodying its institutional sectarianism and systematic violence. He warns of the danger of descending into a “state of nature” (a war of all against all) if the revolution loses its democratic character. With the onset of militarization (2012 onward), he discusses how weapons became necessary for defense, but their unregulated nature paved the way for the escalation into war. He then delves into the “social and cultural roots of Syrian fascism,” considering the regime inherently fascist, relying on absolute violence as its language of power, and supported by a deeply entrenched sectarian structure.

The most devastating blow came with the rise of “militant nihilism” (extremist jihadists like ISIS). He describes it as a direct consequence of the destruction of the peaceful revolution, a second monster trampling its corpse, just like the regime. In a similar vein, he says: “The nihilistic nature of the Syrian regime is its most defining characteristic… a nihilism that expresses itself through the unrestrained and uninhibited use of violence, original in that it is not a reaction to counter-violence, but rather a deliberate choice by the nihilistic regime, which will soon raise a slogan it considers the regime’s political ideology: ‘Assad or no one,’ and its twin, ‘Assad or we burn the country.'”

This quote encapsulates how Haj Saleh views the regime as nihilistic, preferring the destruction of the country to the loss of power.

The book culminates in the concept of the “Three Monsters,” which he coined to describe the forces that have carved up Syria’s carcass:

- The fascism of the Assad state and its allies (Iran, Hezbollah, and later Russia).

- The religious nihilism of the jihadists (ISIS and its affiliates).

- The pragmatism of international powers (the West with its hesitation, and Russia with its direct intervention).

In later essays, he delves into symbols and slogans, explaining how the war fractured Syrian identity: the flag of the revolution versus the flag of the regime, the rural areas that took up arms first versus the cities under regime control. He highlights the absence of organized, democratic political leadership as a primary reason for the revolution’s descent into the sectarian and jihadist trap.

In conclusion, he does not succumb to despair. Although the revolution has become “impossible” in its initial form, it has not died intellectually. Therefore, we see him calling for the rejection of all three monsters and the reconstruction of a pluralistic, secular, democratic Syrian identity based on justice and equality. In one of his introductions or similar statements, he says: “Syria will either be returned to the extremist Assad minority rule, or this rule, under the protection of the bayonets of hostile foreign powers—Russia, Iran, and their proxies—will have extinguished the possibility of genuine political change and the Syrian people’s ownership of that change. This extinguishment, inevitably temporary, must be made available in the form of a book whose pages can be opened and closed.” In this quote, we see how he expresses his hope that the book itself will serve as a tool for preserving the memory of the revolution and the possibility of change.

Its significance in our current context:

After the fall of the Assad regime, the book remains a living testament to the original spirit of the revolution: a popular, liberationist, and non-sectarian uprising. It reminds us that the challenge is not merely the overthrow of the regime, but rather the establishment of a new order. A democratic alternative that transcends the three monsters. Despite the author’s secularism and leftist leanings, reading this book today is essential for any political project seeking genuine national unity and a reshaping of Syrian thought toward a future worthy of the sacrifices of the Syrian people.

This is a book to be read carefully, discussed deeply, and revisited constantly because it doesn’t merely recount history; it asks: How do we understand what happened in order to build what should be?