Political rumors have become a central phenomenon in shaping public opinion and influencing trust in political institutions, especially in our current digital age, where information flows at lightning speed through social media and online platforms. The study of rumors, sometimes referred to as “rumor studies” in academic contexts, is defined as an analytical field that focuses on how rumors originate, spread, and are accepted by individuals, particularly in political spheres where ambiguity and a lack of sufficient information are key contributing factors.

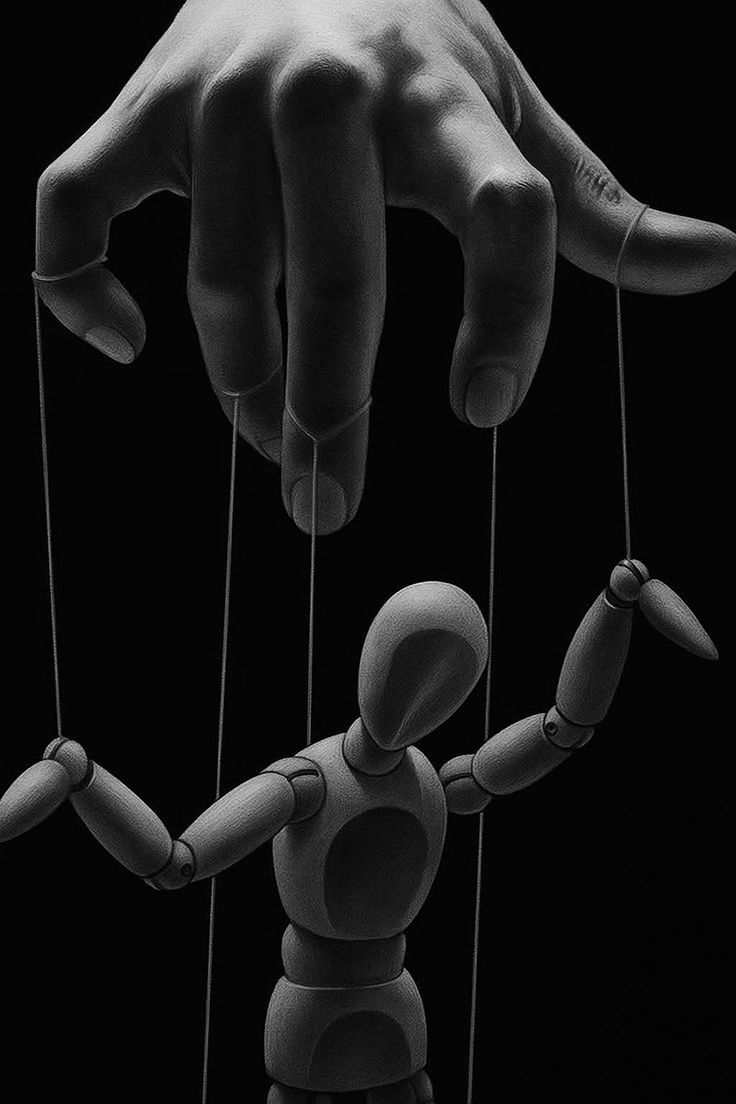

This field is not entirely independent but intersects with political psychology, communication studies, and political sociology, providing a framework for understanding how misinformation transforms into a tool for manipulating public opinion.

In this context, political rumors are considered social and political constructs used to reinforce partisan narratives or weaken opponents, leading to the erosion of trust in democratic processes and the exacerbation of political polarization.

With increasing academic interest in this phenomenon, particularly after events such as the 2016 US elections and the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become essential to explore the causes of rumor spread, their negative impacts, and strategies for combating them through an analytical narrative that connects theory and practical application.

The journey of understanding political rumors begins with examining their historical and psychological origins.

Since ancient times, rumors have been a tool in warfare and politics, as seen in propaganda during the two World Wars, where governments used misinformation to boost morale or instill fear of the enemy.

In the modern era, with the advent of mass media and then digital media, rumors have become even more widespread and influential. Researchers indicate that rumors originate in situations of uncertainty, where individuals seek to fill knowledge gaps with simplistic explanations, often conspiratorial in nature.

For example, during times of crisis, such as elections or pandemics, reliance on rumors increases as a means of interpreting complex events.

Psychologically, conspiratorial thinking plays a crucial role, as people tend to believe that major events are the result of secret plots rather than chance or human error. This tendency is reinforced by strong partisan affiliation, which makes individuals more receptive to rumors that align with their political views and more dismissive of those that contradict them.

Surveys and experiments in recent studies have shown that partisan affiliation explains a significant portion of the acceptance of misinformation, as in the case of rumors about “election fraud” in the United States in 2020, where a large percentage of Republican voters believed that fraud had occurred based on partisan narratives unsupported by evidence.

However, the reasons for the spread of rumors are not limited to individual psychological factors; digital technology plays a pivotal role in accelerating their dissemination. In the age of social media, rumors spread at an astonishing speed thanks to algorithms that prioritize emotionally charged and sensational content, thus amplifying their impact on public opinion.

For example, in the 2016 US elections, misinformation about political candidates spread across Facebook and Twitter (now X), influencing voter behavior.

Studies have also shown that users who are more politically polarized share misinformation more frequently, not due to ignorance, but to reinforce their political identity and attack opponents. This polarization creates a vicious cycle, where the spread of rumors reinforces partisan divisions, leading to greater acceptance of misinformation.

In authoritarian contexts, rumors can be a tool of resistance against censorship, as in China, where they spread through platforms like Weibo to expose corruption or government negligence, taking advantage of the lack of transparency. However, in democracies, they are more dangerous because they target the very foundation of the system: trust in electoral processes and institutions.

The effects of political rumors are multifaceted, beginning with the erosion of trust in institutions.

In democracies, rumors diminish confidence in elections, leading to decreased civic participation and increased skepticism about the legitimacy of the results. For example, after the spread of misinformation about the 2020 US elections, trust in the integrity of the elections plummeted among some groups, with the belief that their vote was ineffective. This is where the danger lies, as this erosion threatens the core of democracy, which depends on an informed and engaged citizenry.

In authoritarian regimes, rumors reduce support for the system. Empirical studies in China have shown that exposure to anti-government rumors significantly reduces trust in policies, even among members of the ruling party.

These effects accumulate with repeated exposure, further reinforcing doubts about legitimacy.

In addition, rumors increase political polarization, fueling hatred and hostile rhetoric, which complicates dialogue and exacerbates social tensions. Recent studies (all cited in the references) have found that the sharing of misinformation is higher among conservative or right-wing users in some contexts, leading to disproportionate penalties from platforms and accusations of bias.

This polarization is not neutral; in the United States, for example, conservatives share links to low-quality news sites more often than liberals, even when evaluated by a politically balanced audience.

Socially, rumors influence collective behaviors, as seen during pandemics where rumors about vaccines spread, leading to vaccine hesitancy and exacerbating health crises.

In the political context, they can lead to violence, as in the 2021 Capitol riot, which was fueled by false narratives about the election.

Economically, rumors have caused market volatility or a loss of confidence in economic policies.

To understand these effects more deeply, we must consider the academic definitions of the related terms.

Experts define misinformation as false or misleading information, whether unintentional (misinformation) or intentional (disinformation), with agreement that conspiracy theories and lies are part of it. Factors determining its acceptance include partisan bias, confirmation bias, and a decline in institutional trust, with proposed solutions such as changes in platform design and enhanced media literacy education.

As an applied case study of the principles of rumor theory in a political context, the Syrian reality from the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011 to the present day (2026) provides a living example of how rumors are used as a tool in political and social conflicts.

The revolution began with peaceful protests that quickly transformed into an armed conflict, where rumors played a major role in mobilizing public opinion against the revolution and the people, such as rumors of “sexual jihad” or describing the peaceful revolutionaries at the beginning of the movement as terrorist groups.

As the years passed, especially after the intervention of external powers such as Russia and Iran, rumors became a more deeply ingrained tool of propaganda. The opposition was accused of “foreign conspiracy” or links to terrorism, leading to increased sectarian polarization and the erosion of trust in independent media sources.

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 marked a major turning point, with Ahmed al-Sharaa (formerly known as Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) assuming power as interim president, attempting to rebuild the state with a focus on stability and international relations. However, rumors continued to threaten this transition, especially with real assassination attempts by the Islamic State (ISIS) in 2025. Two attempts were thwarted in Damascus and Idlib, as reported by official Syrian sources.

In 2026, rumors escalated regarding Iranian attempts to assassinate Al-Sharaa, as warned by Israeli intelligence, reflecting regional tensions with Iran, a former supporter of Assad.

The latest of these rumors surfaced in January 2026, when AI-generated fabricated images circulated showing Al-Sharaa injured in a Turkish hospital after clashes inside the presidential palace. These images were debunked by fact-checking platforms such as “Taakkad,” which confirmed that the images were manipulated and originated from old photos from Kuwait in 2020.

These rumors reflect systematic strategies to destabilize the situation, exploiting information vacuums during the transition period to fuel doubts about the legitimacy of the new regime, leading to increased sectarian and regional tensions, and highlighting the need for rapid verification mechanisms to counter disinformation in post-conflict contexts.

In the face of these challenges, the need for effective counter-strategies becomes apparent.

Debunking rumors is not easy, as they often continue to have an impact even after correction, due to the psychological phenomenon of the “continued influence effect.”

In authoritarian contexts, governments rely on official responses, but studies show that responses not supported by strong evidence do not restore trust.

Instead, responses should be detailed and issued by independent sources.

In democracies, it is advisable to focus efforts on non-partisan groups, paying attention to the messenger before the message. For example, neutral experts can be more effective in refuting rumors.

It is also recommended to enhance media literacy to increase awareness of information verification and to regulate platforms to limit the spread of misleading content without restricting freedom of expression.

Multiple studies have highlighted the need for interdisciplinary research to develop better detection tools, with a focus on studying long-term effects.

These strategies require a balance between freedom and security to ensure that democracy is protected from the dangers of misinformation.

In conclusion, the study of rumors in political practice is a vital field for understanding contemporary challenges, as rumors shape public opinion and affect the stability of systems.

Despite their benefits in some contexts for uncovering the truth, their negative impacts outweigh the positive ones, requiring continuous research and practical efforts.

Researchers should also focus on cultural and technological contexts to develop effective solutions while preserving freedom of expression.

References:

- Altay, Sacha, Manon Berriche, Hendrik Heuer, Johan Farkas, and Steven Rathje. “A Survey of Expert Views on Misinformation: Definitions, Determinants, Solutions, and Future of the Field.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 4, no. 4 (2023): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-119.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Barbara Pfetsch. “Misinformation, Disinformation, and Fake News: Lessons from an Interdisciplinary, Systematic Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 48, no. 2 (2024): 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2024.2323736.

- Berinsky, Adam J. Political Rumors: Why We Accept Misinformation and How to Fight It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023.

- Mosleh, Mohsen, Qi Yang, Tauhid Zaman, Gordon Pennycook, and David G. Rand. “Differences in Misinformation Sharing Can Lead to Politically Asymmetric Sanctions.” Nature 634, no. 8034 (2024): 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07942-8.

- Osmundsen, Mathias, Alexander Bor, Peter Bjerregaard Vahlstrup, Anja Bechmann, and Michael Bang Petersen. “Partisan Polarization Is the Primary Psychological Motivation behind Political Fake News Sharing on Twitter.” American Political Science Review 115, no. 3 (2021): 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000290.