Introduction:

Today, hopes for salvation intersect with the complexities of the political and social reality. The country is no longer governed by a single central authority, but rather is divided among multiple entities, each with its own vision and practices. As Syrians aspire to a more just and dignified future, the issue of human rights emerges as one of the most important challenges that cannot be postponed or ignored.

This article seeks to analyze the reality of human rights in Syria during the transitional period, amidst the multiple de facto authorities. It is based on the premise that the issue of human rights is paramount and more important than any other reality. Indeed, we can accept a fragmented reality in which human rights are embedded, despite a healthy political reality in which they are not guaranteed. The article also raises fundamental questions about the possibility of building a unified human rights system in a fragmented country, and offers practical visions and recommendations for moving toward a future worthy of the sacrifices of the Syrians.

First, the heavy legacy of human rights violations in Syria:

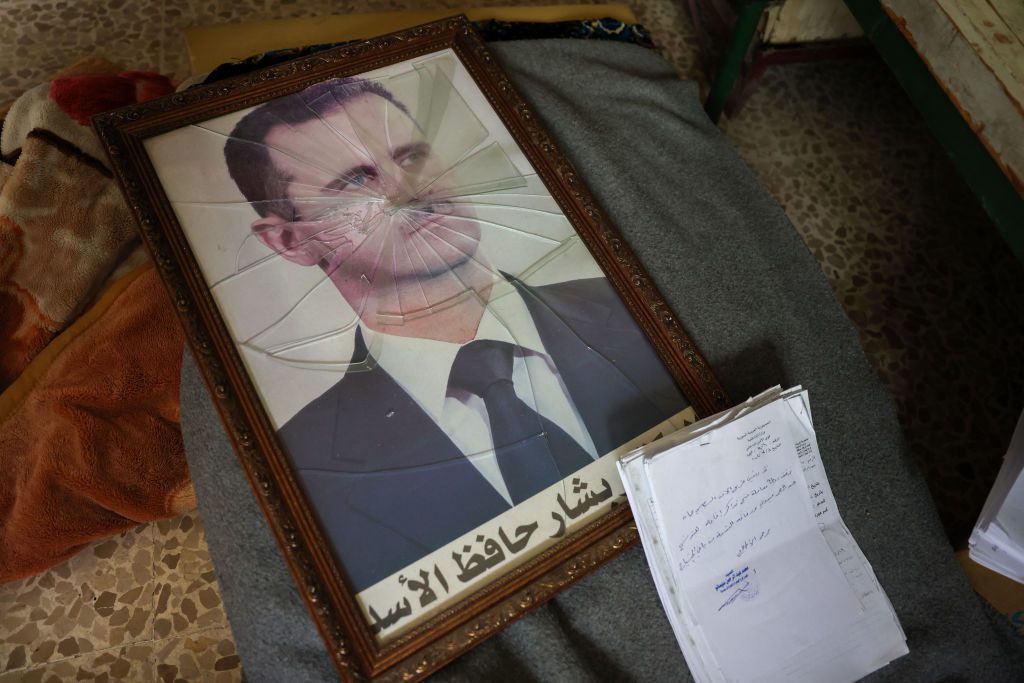

Before 2011, Syria was governed by a strict security grip, where human rights violations were part of the political system’s fabric. Arbitrary arrest, torture, the absence of freedom of expression, and restrictions on civil society activities were daily practices, carried out under the guise of “state security” and “national interest.”

With the outbreak of the revolution, these practices not only changed but escalated to an unprecedented degree. Prisons were transformed into cemeteries, homes into military targets, and cities into battlefields. Multiple parties entered the conflict, each committing violations against civilians, making the human rights situation even more complex and intertwined.

Today, after more than a decade of conflict, it is impossible to discuss Syria’s future without confronting this heavy legacy and recognizing that justice is not a luxury, but an existential necessity.

Second, the multiple authorities and the divergence of legal references:

The transitional authority in Damascus:

Despite the collapse of the former regime, Damascus remains under the control of a transitional authority attempting to rebuild a shattered state. This unifies the majority of Syrians, especially the revolutionaries, with the support of this authority. However, although this authority speaks of “reforms,” its practices on the ground have not established their foundations. Furthermore, despite all the efforts and hopes, they do not herald a radical transformation for many reasons. However, from the detainees in Idlib before the liberation, and even the individual cases used to justify abuses, to the experience of Syria at its inception, where it shifted toward tyranny, all of this highlights the need to monitor the performance of this authority from a human rights perspective and hold it accountable for its commitment to international standards, especially with regard to freedom of expression, judicial independence, and the rights of political detainees.

The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in al-Jazeera:

In northeastern Syria, the SDF administers a large area under the umbrella of the “Autonomous Administration.” Although this administration presents itself as a democratic model, the reality points to significant challenges.

There are clear efforts in women’s empowerment, education, and community engagement. However, there are also reports of arbitrary arrests, restrictions on press freedom, and security practices that are not significantly different from traditional regimes.

Perhaps the challenge here lies in balancing security and building a genuine human rights model, especially given the region’s ethnic and religious diversity.

Local Governance in Sweida:

Sweida, with a Druze majority, has witnessed remarkable transformations in recent years, with the emergence of semi-autonomous local governance systems independent of Damascus.

This model, despite its limitations, replicates what Syrians overcame during the revolution: the establishment of a civil authority based on identity that neither cares nor respects rights, relying instead on popular representation. This model also highlights the challenges that remain, most notably the scarcity of resources, the absence of international support, the overlapping influence of security forces, and the return of fugitive former regime officials.

Third, Transitional Justice as an Approach to Rebuilding Rights:

Transitional justice is an integrated system that aims to address the effects of violations, redress harm, and ensure non-recurrence. In the Syrian case, transitional justice appears to be an urgent necessity, but it faces enormous challenges.

First, there is no unified authority capable of launching a comprehensive national process, despite the strength and rigidity of the Damascus government compared to the SDF and the rebels in Sweida.

Second, there is a deep societal divide, making reconciliation complex.

Third, there are international and regional interferences that hinder any independent process.

However, small steps can be taken, such as documenting violations, providing psychological and social support to victims, and launching local reconciliation initiatives.

Civil society can also play a pivotal role in this area by building human rights networks, organizing awareness campaigns, and providing legal support.

Fourth, Structural and Cultural Challenges:

Human rights cannot be discussed in isolation from the political and cultural structure. In Syria, there are profound structural challenges, most notably:

- The absence of a unified authority makes the implementation of any human rights system nearly impossible.

- External interference is reshaping the political landscape according to international interests, not the needs of Syrians.

- Societal divisions: sectarian, ethnic, and political, weaken any attempt to build a comprehensive human rights discourse.

- The weakness of judicial, educational, and media institutions makes disseminating a culture of rights difficult.

However, there are also cultural challenges, such as the traditional view of authority, the absence of a culture of accountability, and fear of change.

These challenges require long-term work, beginning with education, moving on to the media, and culminating in the building of truly democratic institutions.

Conclusion:

In a previous article published on our website entitled “On Human Rights Day: Syria is the Gateway to a New Era of Human Barbarism,” we emphasized that the absence of human rights in Syria is the cause of barbarism and corruption. To overcome this, we, at the Scientific Office of the Syrian Future Movement, recommend the following to build a human rights future:

Drafting a National Human Rights Charter:

Political and civil forces must agree on a comprehensive human rights charter that defines fundamental principles that cannot be compromised, such as freedom of expression, equality, and justice.

Involving Local Communities:

It may be difficult to build a human rights system from the top down, so we believe it is essential to involve local communities in formulating policies, setting priorities, and monitoring performance.

Supporting Independent Media:

The media is a tool for raising awareness, exposing violations, and stimulating public debate. Independent platforms must be supported, and journalists must be protected.

Promoting Human Rights Education:

Human rights concepts must be integrated into school curricula, teacher training must be provided, and workshops must be organized for youth.

Empowering Women and Youth:

A human rights-based future cannot be built without the inclusion of marginalized groups. Therefore, women and youth must be supported in political, civil, and media work.

Conclusion:

Talking about human rights in post-Assad Syria is not an intellectual luxury, but an existential necessity. The future is not built solely on the ruins of the past, but rather on a clear vision that restores human dignity and establishes a new social contract.

Despite the enormous challenges, the opportunity still exists. Syrians, who have paid a heavy price, deserve a better future in which their rights are respected, their freedoms are protected, and those who violated their dignity are held accountable.

Building a new Syria begins and ends with the people, and every step toward justice is a step toward true peace.

Dr. Zaher Badrani

Chairman of the Syrian Future Movement