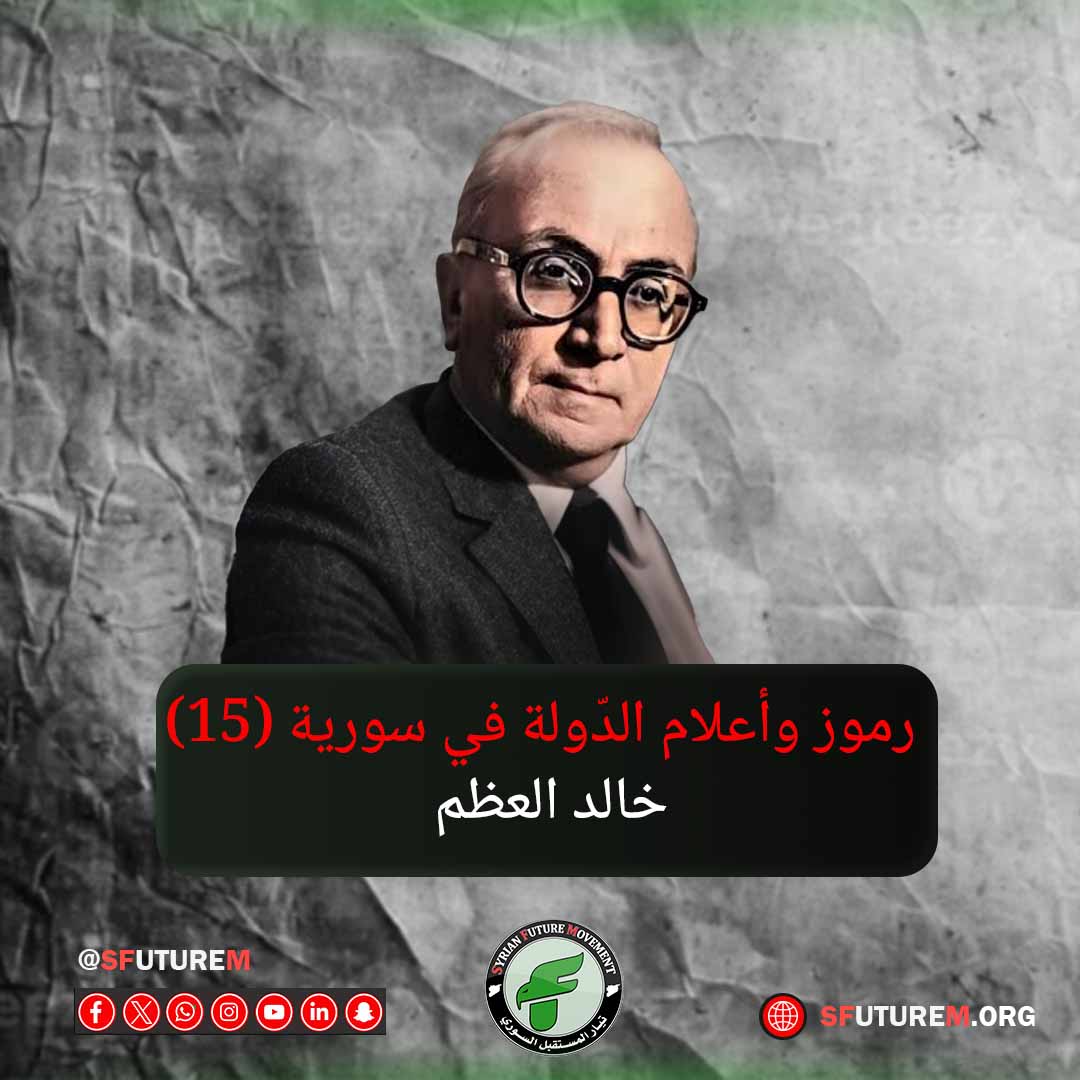

Symbols and Figures of the State in Syria (15): Khalid al-Azm

- He was born on November 6, 1903, in Souq Sarouja, Damascus.

- His family, the distinguished “Al-Azm” family of Damascus, had five members who served as governors of Damascus during the Ottoman era, the most famous of whom was As’ad Pasha, who ruled for 14 years. During his rule, Al-Azm Palace and Khan As’ad Pasha were built, along with other improvements to the city’s infrastructure.

- His father, Muhammad Fawzi Al-Azm, served as the mayor of Damascus, during which he accomplished many projects, such as the National Hospital, bringing water from Ain al-Fijeh, and contributing to the construction of the Hejaz Railway. He was elected twice as a member of the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies, representing Damascus, and was also appointed Minister of Religious Affairs.

- He received his primary education from private tutors between Damascus and Istanbul after his father was appointed Minister of Religious Affairs.

- After his family returned from Istanbul, he studied at the Commercial School and then studied law at Damascus University, graduating in 1923.

- He inherited his father’s political work early on, becoming a minister in the Damascus Federal Government during the era of the Syrian Union.

- Throughout that period, he managed his family’s vast estates throughout the country and kept himself away from politicians close to the French Mandate over Syria.

- He had a good relationship with Hashim Al-Atassi and Shukri Al-Quwatli, but politically, he was closer to Hashim Al-Atassi, who opposed the project of unity with Egypt.

- During his ministry, he established the Damascus Chamber of Industry in 1935, having previously established the government cement factory in 1930.

- After the declaration of the First Republic in 1932, he became a member of parliament representing Damascus.

- He was appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the government of Nasuhi Al-Bukhari in 1939.

- Despite being a capitalist, his financial policies also supported balanced development and worked to ensure fairness for the poorest segments of the population.

- He initiated the alliance between Syria and the Soviet Union and had a special friendship with the Maronite Patriarch Paul Peter Meouchi.

- After the dismissal of Bahij Al-Khatib in 1941, in a French attempt during World War II to win over national political forces in Syria, he was entrusted with the presidency of the Syrian state on an acting basis, holding both the positions of President and Prime Minister.

- He formed his first ministry, with the task of preparing for the return of constitutional life to the country.

- He issued a general amnesty for all political detainees imprisoned by Vichy France.

- He safeguarded the country from the repercussions of Rashid Ali Al-Gaylani’s coup in Iraq, though France pursued a policy of delay and procrastination.

- France replaced him after five months with former President Taj al-Din al-Hasani.

- He was elected as a member of parliament in 1943 and was re-elected several times.

- In the first independence government in 1946, he became Minister of Justice, and one of his first decisions was to abolish the “foreign privileges in the country.”

- He led the opposition against Shukri al-Quwatli when the latter sought to amend the constitution to allow himself to run for a second term. However, al-Quwatli succeeded in amending the constitution and won the presidential election in 1947, defeating Al-Azm.

- He accepted the position of Syrian ambassador to France but did not stay in the role for long, as al-Quwatli soon asked him to form a government. This became his second government, but it was not supported by the major political blocs, causing it to collapse ten days after its formation.

- He returned to his position as ambassador in France and succeeded in securing an arms deal with them. Later, he also secured another arms deal with the Soviet Union.

- Regarding currency reform, Al-Azm’s government issued a series of decisions and legislations aimed at canceling the Syrian Bank’s right to issue currency and restricting this right solely to the Syrian state, through an exclusively Syrian institution called the “Syrian Currency Issuance Institution.”

- Al-Azm’s monetary revolution led to an increase in the value of the Syrian lira, which came to equal more than 405 milligrams of gold.

- The Nakba of Palestine led to a series of disturbances and riots in various Syrian cities, after which Jamil Mardam Bey’s government resigned, and Al-Azm was tasked with forming a new government.

- His government failed to make any progress in quelling the public outrage over the defeat.

- Some politicians called on former President Hashim al-Atassi to form a crisis management government, and al-Atassi was tasked with this but declined.

- Al-Quwatli tasked Khalid al-Azm with forming the government, but he declined the assignment. The responsibility was then given to Prince Adel Arslan, the Minister of Social Affairs, but he also failed. Finally, President al-Quwatli re-tasked Al-Azm, who accepted this time and successfully formed his third coalition government on December 16, 1948.

- The government received a vote of confidence with a majority of 73 votes out of the 108 deputies present at the session.

- Al-Azm’s third government faced numerous challenges related to the importance of arming the military, stopping the riots, and preventing the collapse of the Syrian lira, in addition to its commitment to “liberating Palestine” as stated in its ministerial statement.

- The Syrian press, across its various spectrums, welcomed this formation, especially after the government succeeded in restoring stability to the lira and halting the riots. In foreign policy, Al-Azm declared that the world had become divided into two blocs and that Syria could no longer remain neutral, thus it had to choose between the United States or the Soviet Union.

- During this period, the government approved the financial agreement with France and began studying the Tapline pipeline project.

- These steps led the government to face criticism from the People’s Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, accusing the country of becoming subordinate to the United States.

- The country witnessed mass protests in Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, and several other areas against the Tapline agreement, which was described as costly and unbeneficial to the Syrian economy. This pushed the government to withdraw it from circulation and postpone its approval.

- Among the accomplishments of Al-Azm’s government were securing a French arms deal, approving the 1949 armistice agreement with Israel, ratifying the Syrian currency agreement, as well as establishing the National Chamber of Agriculture, building grain silos in the eastern region, and establishing a national textile factory to produce affordable national clothing after prices had risen in the Syrian market.

- On March 6, Interior Minister Adel Al-Azm resigned due to the halting of protests against the Tapline agreement, the temporary closure of schools, and the revocation of the license of an opposition newspaper. He was replaced by Mohsen Al-Barazi.

- The House of Representatives called for a session to discuss the army, but Al-Azm refused, stating that the army should be kept out of political conflicts.

- The Parliament held its session without the government’s presence, where harsh criticisms were directed at the army and its leadership, laying the groundwork for Hosni Al-Zaim’s coup later on.

- Four months after forming his third government, on March 30, 1949, the army, led by Hosni Al-Zaim, overthrew the constitutional government, arresting both the president and the prime minister and placing them in Mezzeh Military Hospital.

- On the same day, Al-Quwatli resigned from the presidency, and Al-Azm from the premiership, following a visit by Fares Al-Khoury to both in prison.

- Their resignations were published on April 6, and Al-Azm was later released.

- After Al-Zaim’s removal in August 1949 by another coup led by Sami Al-Hinnawi, restoring constitutional rule, Al-Azm was appointed Minister of Finance in the crisis management government formed by Hashim Al-Atassi on August 15, 1949.

- One of the first tasks of the crisis management government, in which Al-Azm participated as Minister of Finance, was preparing for the elections of the Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution for the country.

- He ran as an independent candidate from Damascus and succeeded again.

- After the Assembly convened, Hashim Al-Atassi was elected president of the republic, which had previously been governed by the military leadership. After his election, Al-Atassi tasked Al-Azm with forming a government.

- Al-Azm accepted the task of forming the government but was unable to do so and apologized the next day.

- Al-Atassi then tasked Nazim Al-Qudsi, the head of the People’s Party, with forming a government, but he also apologized the following day due to the army’s leadership interfering in the distribution of names and positions.

- Al-Atassi wanted to resign but retracted his resignation under pressure from the army and tasked Al-Azm again, who successfully formed a government on December 29, 1949, that was acceptable to both the army and the People’s Party.

- This period was extremely delicate in Syrian politics. After the ousting of Hosni Al-Zaim and the return of constitutional rule, the army turned on itself, arresting Sami Al-Hinnawi, with Adib Al-Shishakli becoming the army commander and intervening in the most intricate details of Syrian political life. This was rejected by most political parties and led to instability in the country.

- On January 4, 1950, Al-Azm’s government sought a vote of confidence, and its ministerial statement did not include any reference to unity with Iraq or broader “Arab unity.”

- The government faced criticism from the People’s Party and the Republican Bloc, but it nonetheless secured confidence with 92 votes in favor, 7 against, and 33 deputies absent from the session.

- Al-Azm’s fourth government did not last long either, remaining in power for six months before resigning on June 4, 1950.

- Al-Azm’s government was accused of lacking neutrality, opposing the People’s Party, which held the largest bloc in parliament, and aligning Syria with the Saudi-Egyptian axis as opposed to the Hashemite Iraqi-Jordanian axis.

- Al-Azm managed to navigate through this issue, stating that he accepted support from any country that offered it.

- He played a role in the discussions surrounding the new constitution, aiming to distance Syria as much as possible from Arab axes and specific economic ideologies.

- On April 26, Defense Minister Akram Hourani resigned following disagreements with several ministers, weakening Al-Azm’s government due to Hourani’s leadership of the “Republican Bloc,” which enjoyed full support from the military.

- Al-Azm traveled to Egypt to attend an Arab League summit and then to Riyadh. On May 24, new disputes arose within the government, and as a result, Al-Azm’s government resigned on May 28, 1950.

- Atassi requested Al-Azm to form a new government, but he declined, and the position was given to Nazim Al-Qudsi, the head of the People’s Party, who opposed the military. This was the first opportunity for the People’s Party, the largest parliamentary bloc, to form a government despite the military’s opposition.

- Al-Azm remained out of office for less than a year. On March 27, 1951, he formed his fifth government after eighteen days of consultations due to intense disagreements between the military, the presidency, and parliament.

- This fifth government, like its predecessor, operated during the period of Adib Al-Shishakli’s first coup, which maintained a civilian government under military oversight, before Al-Shishakli launched his second coup, directly seizing control of the government.

- The tenure of this government lasted only five months. It consisted of seven members, all independents except for one representative of the army as Defense Minister and one representative of the Arab Socialists.

- The government secured confidence with a vote of 52-0, with 4 abstentions and the rest absent.

- During the discussion of the government’s statement, Israel bombed locations near Lake Hula, expediting the vote of confidence for the government.

- Under pressure, Al-Azm’s government promoted Adib Al-Shishakli to the highest military ranks, appointing him as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces.

- The government also approved a new arms deal worth $1.4 million to strengthen the military.

- During its tenure, Al-Azm’s government closed the borders to Lebanese goods in an attempt to prevent the collapse of local industry due to the influx of Lebanese imports, effectively ending the economic union with Lebanon.

- The government announced the establishment of the Latakia port and implemented economic reforms for the Syrian lira. It also introduced a project to extend railways between the eastern regions along the Euphrates River and Latakia to facilitate import and export movement.

- The opposition, led by the People’s Party, nominated Ma’ruf Al-Dawalibi for Speaker of the House, while the government put forward a candidate close to Al-Azm. After two rounds of voting, Al-Dawalibi won, marking a setback for the government.

- What ultimately brought down the government was the parliament’s refusal to approve the exceptional expansion of military spending.

- President Atassi offered al-Azzam the choice to either resign or present a financial project acceptable to the House of Representatives, and when a formula could not be reached, al-Azzam resigned on July 31, 1951.

- Just four months after the resignation of the government, Adib al-Shishakli staged a coup against the constitutional rule, appointing Fawzi al-Sulh as president with executive and legislative powers, suspending the constitution, dissolving the House of Representatives and political parties, and forcing President Atassi to resign.

- During the four-month period, three governments succeeded one another, led by Hassan al-Hakeem, Zaki al-Tayeb, and Ma’ruf al-Dawalibi, highlighting the instability the republic experienced due to military intervention in politics.

- Following the coup, most political leaders, including al-Azzam, withdrew from political activity.

- After the establishment of al-Shishakli’s regime, he requested al-Azzam to form a civilian government, but al-Azzam refused, citing health reasons for his refusal.

- He boycotted the legislative elections in 1953, and the political boycott continued until February 26, 1954, when al-Shishakli stepped down from power.

- He participated in the legislative elections of 1954, which brought him back to parliament and he chaired the “Democratic Bloc” consisting of 37 independent deputies, making it the largest bloc in parliament.

- Atassi tasked him with forming a government after the elections, but he failed after two days of negotiations with the People’s Party on one side and the Ba’ath Party on the other.

- He supported the government formed by Faris al-Khouri at that time, and the Democratic Bloc was described as a right-wing bloc supportive of the West against leftist blocs supportive of the East.

- Al-Azzam returned to the executive authority again on February 13, 1955, as Minister of Foreign Affairs and a partner in the government formed by Said al-Ghazzi ahead of the presidential elections, which brought him closer to leftist forces in the country.

- The al-Khouri government resigned in February 1955 after the parliament, with a majority of independent deputies along with the Ba’athists and Communists, rejected the budget proposed by the government.

- A new government was formed under the presidency of Sabri al-Asali, in which al-Azzam served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Acting Minister of Defense, during which the assassination of Adnan al-Maliki occurred, and it continued its duties for more than six months.

- The government did not resign until after the 1955 presidential elections, which resulted in the victory of Shukri al-Quwatli in the second round of voting, with Khalid al-Azzam being his only competitor.

- Al-Azzam returned to the executive authority again on February 13, 1955, as Minister of Foreign Affairs and a partner in the government formed by Said al-Ghazzi ahead of the presidential elections, which brought him closer to leftist forces in the country.

- Al-Azzam retired briefly after his loss but returned again in November 1956 to join Sabri al-Asali’s government as Minister of Defense during a coalition government of the Ba’ath Party, the National Bloc, and the “Democratic Bloc,” which included several independent deputies.

- He played a key role in achieving an alliance with the Soviet Union, traveling numerous times to arrange loans, economic agreements, and arms deals, which angered the United States.

- Socialists lost trust in him due to his wealthy aristocratic and Ottoman background, and despite not being an advocate of absolute capitalism and sometimes aligning with the Soviet Union, he earned the nickname “the Red Millionaire.”

- The Syrian press adopted this nickname for al-Azzam during the 1950s because he was not a socialist.

- He opposed, without success, the union with Egypt in 1958, which led to the declaration of the United Arab Republic, arguing that Nasser would destroy the democratic system and free market economy in Syria.

- Al-Azzam’s political career reflects the complex dynamics of Syrian politics during a tumultuous period marked by military coups and ideological struggles.

- He retired from political life during the union and emigrated to Lebanon.

- When the separation occurred due to a military coup led by Abdel Karim al-Nahlawi with 35 officers, which announced the dissolution of the relationship with Egypt, al-Azzam returned to Syria.

- He helped draft the separation document himself and attempted to run for the presidency, but the army rejected his candidacy.

- Nazem al-Qudsi was elected president, and al-Azzam returned to parliament as a deputy for Damascus.

- On March 28, 1962, another coup overthrew the regime, and both al-Qudsi and al-Azzam were imprisoned.

- On April 2, a counter-coup released them, and al-Azzam became prime minister again under al-Qudsi’s rule.

- The two men allied with former president Shukri al-Quwatli to rid the army of Nasserists and reversed the nationalization project put in place by Gamal Abdel Nasser when he was president of the United Arab Republic.

- Before achieving this, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party came to power through the March 8 Revolution, and both al-Azzam and al-Qudsi moved to Lebanon.

- Khalid al-Azzam’s move to Beirut was permanent, where he lived under difficult financial conditions, as the Ba’ath Party seized his assets in the country.

- In 1964, he began publishing his political memoirs in the newspaper An-Nahar, which were linguistically edited by Khalil Klass, and the publication continued even after his death.

- He died in Beirut and was buried there on November 18, 1965.

- In his will, he requested to be buried near Imam al-Awzai in Beirut and not to be taken to Damascus to avoid unrest in the city and among his supporters, which could lead to gunfire and casualties.

- In the book “Al-A’lam” by Khair ad-Din al-Zurqali, it is mentioned that his wife sold his memoirs after his death, and it is said that they underwent alteration and changes, with some parts published serially in An-Nahar and later published in full in a book.

- His personality was referenced in the series “Hamam al-Qishani,” which chronicled the political life in Syria from the era of the Syrian Kingdom to the Ba’ath Revolution and the establishment of the Second Republic.

- His character is described as one of the most problematic and enigmatic figures in contemporary Syrian history.

In the Syrian Future Movement (SFM), as we commemorate the founding statesmen of Syria, we invoke one of the influential figures in Syria, a symbol of the early Syrian state who contributed to shaping its structure, the national leader ‘Khalid al-Azzam.’ This is part of a sequential file we present to you, which includes symbols and icons of the Syrian state, reflecting our desire to connect our contemporary revolutionary present with a solid past and historical milestones. We hope to instill in our people the need to build and cultivate distinguished statesmen, learning from their experiences, overcoming their shortcomings, and building upon their history to preserve the homeland, safeguard our achievements, and restore the pride and glory of the Syrian state after years of oppression, tyranny, and corruption.